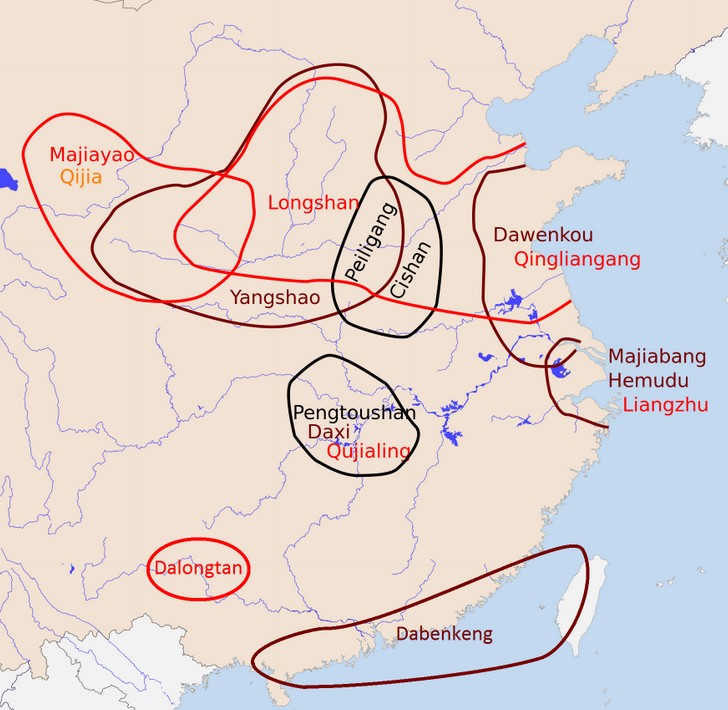

The Dawenkou culture was a Chinese Neolithic culture primarily located in the eastern province of Shandong, but also appearing in Anhui, Henan and Jiangsu. The culture existed from 4300 to 2600 BC, and co-existed with the Yangshao culture. The Yangshao culture existed extensively along the middle reaches of the Yellow River in China from around 5000 BC to 3000 BC. The culture is named after the Yangshao site, the first excavated site of this culture, which was discovered in 1921 in the town of Yangshao in western Henan by the Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960). The culture flourished mainly in Henan, as well as the neighboring provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi further inland and to the west of the Dawenkou culture.

The advanced pottery techniques of the Dawenkou culture (c. 4300–2600 BCE) do seem somewhat anomalous in the broader timeline of Chinese ceramics, as their thin-walled and refined vessels appear to surpass those of many contemporary cultures and were not immediately followed by widespread technological adoption. Scholars have explored several possible explanations for this

The Dawenkou people had a highly stratified society, as seen in their burial practices, which included elaborate grave goods. High-status individuals were often buried with finely crafted pottery, suggesting that elite demand may have driven the refinement of ceramic production.

Some of their most delicate pottery may have been prestige items, meant for ritual or ceremonial use rather than everyday function. If this was the case, the techniques may have remained specialized and not diffused widely into common pottery-making traditions.

The Dawenkou culture existed primarily in the Shandong and surrounding regions, meaning its ceramic advancements were localized.

Unlike the later Longshan culture (c. 3000–1900 BCE), which had wider influence and is often credited with more advanced pottery techniques, Dawenkou's refinements may not have been widely adopted due to isolation or limited cultural transmission.

If these techniques relied on specific materials, tools, or artisan knowledge, they could have been lost when the culture declined.

While some Dawenkou pottery exhibits symmetry and surface refinement suggestive of rotational forming, it does not appear that they used a fast-spinning potter’s wheel.

Their use of slow-turning devices or rotational smoothing may have been an experimental or short-lived development that did not become a widespread practice.

Without the mechanical efficiency of a fast wheel, producing thin-walled ceramics would have remained labor-intensive, limiting its broader adoption.

The Longshan culture (c. 3000–1900 BCE) gradually replaced the Dawenkou culture in the same region and developed a different ceramic tradition.

Longshan pottery included eggshell-thin black wares, which were also finely made but used different techniques and aesthetic preferences.

It is possible that instead of direct continuity, Longshan potters rediscovered or reinvented refined pottery techniques rather than inheriting them directly from Dawenkou traditions.

If Dawenkou’s advanced pottery techniques were practiced by a specific artisan class or workshop tradition, knowledge could have been lost due to social changes, population shifts, or external pressures.

Unlike later dynastic periods where knowledge was systematically recorded and transmitted, Neolithic pottery skills would have depended on oral traditions and apprenticeship, making them more vulnerable to disruption.

The refined Dawenkou pottery appears to have been a localized innovation, possibly driven by elite or ritual use, but it did not become a dominant ceramic tradition due to technological limitations (absence of the fast wheel), regional isolation, and the later transition to Longshan cultural influences.

While some elements of their craftsmanship may have influenced later developments, there was no direct continuity, and their pottery style largely faded after their decline.

A