ACRYLIC ON CANVAS / MURALS

This page is dedicated to one of the many talented individuals who stood up and added their special magic to make this project what it was. With very limited means, the Historical Reconstruction Artist Lars Gillis Larsson helped create visual images of how things had been, and what they would look like if we managed to build the ship and undertake the journey.

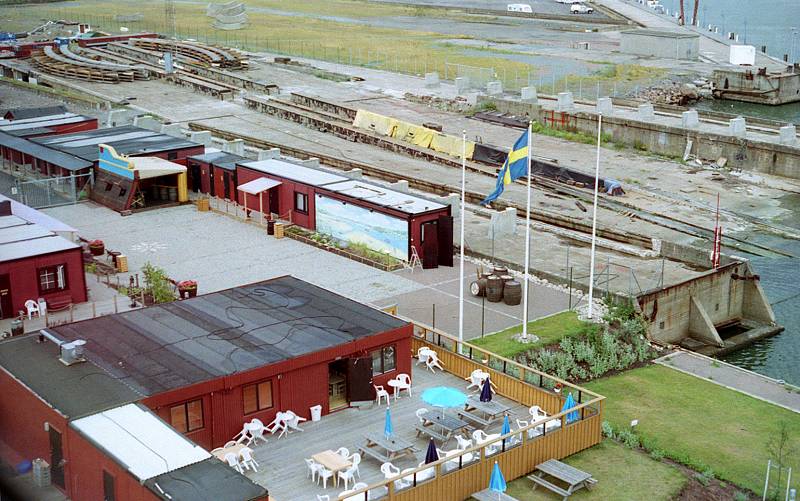

Since the project was initiated by a small group of enthusiasts with an idea and a muddy plot of industrial wasteland borrowed from the Eriksberg Development Co., there was very little to show the few visitors we managed to attract to take a look at our endeavors.

During the first few years, there was nothing even remotely resembling a ship to look at. All we could do was share our dream and try to help our visitors see it too. Once we at least got the setting up of the shipyard started, Lars Gillis' talent became crucial in illustrating the next steps. During these years, the shipyard was our second home, and I personally cannot imagine the project without his paintings.

A web page dedicated to his work is long overdue.

The Shipyards Café door is embellished with a trompe-l'œil of a ship's window.

Acrylic on plywood. Painting by Lars Gillis, 1996.

One day we found Lars Gillis just standing there fully equipped with paint and brushes, brightening up the inside of the shipyard café door with a trompe-l'œil painting of a ships window, and the happy face of the project founder Anders Wästfelt peering in.

In the background the 7 meter long view of the Gothenburg harbor entrance can be partly seen displayed on the souvenir shop wall. Both paintings probably lost when the shipyard was demolished.

The first concern when planning the shipyard area was to make it a nice and interesting place to visit. This was an absolute necessity since that was how the sponsors eventually would be met and introduced to the project for many years to come. The problem of how to make everybody else see what we saw, was much helped by Lars Gillis.

The Göta Älv and the Gothenburg Harbor Entrance

Looking up the Göta Älv towards the City of Gothenburg.

Acrylic on hardboard, 2x7 meter, 1996.

For a modest compensation that barely covered the cost of paint, Lars went ahead and painted this mural. Unfortunately, the mural was lost or discarded when the shipyard was demolished. It was acrylic on hardboard, measuring 2x7 meters, created in 1996. There's a rumor that Anders salvaged this painting when he moved to Liden, near Sundsvall, but it supposedly got destroyed in the process. It's said that Lars Gillis visited Anders' place and painted a new one. However, this will need to be confirmed though. I would not have been surprised.

The Göta Älv and the Gothenburg Harbor Entrance

Mid part of souvenir shop wall mural. The flower bed in front of the painting is made

to interact with the painting and to create a three dimensional effect.

Shipyard in 1996, showing in painful detail the necessity of storytelling

Immediately facing any visitor entering the shipyard from its main entrance was this 2 x 7 meter long mural showing the Gothenburg harbor entrance as it should have looked at the time of the homecoming of the Gotheborg in 1745. It was displayed on the wall of the Shipyard's souvenir shop. This was the natural meeting place and the starting point for all guided tours of the shipyard.

Ship's provision

Reconstruction painting for the book "Jan-Erik Nilsson: Food on-board Swedish East Indiamen (MS)".

Painting in acrylic on canvas, by Lars 'Gillis' Larsson

One of the things that captivated the imaginations of the visitors was to listen to how the crew lived on-board, and how live farm animals in large numbers were kept on-board together with the sailors, to provide fresh eggs, milk and to eventually be eaten along the road. When this picture was painted the keel was just barely laid out and there were no way to really know how the ship would look inside. But Lars Gillis could help. It eventually turned out to be remarkable correct. Lars was personally very proud of this picture that indeed turned out very well, but was also half ashamed that he taken some artistic liberties in that in reality the live stock was kept in the middle of the ships hull as in barnyard style, and not near a canon port like this, however, I still think it communicates the general idea very well.

However, you would in reality be sleeping along the walls in a barnyard with animals doing what animals do when they have eaten - or drinking. It would have been very, very crowded with a crew of 140 persons, all this live stock and as much cargo and luggage that you could possible bring. Also most culinary efforts from the ship's cooks side would probably also have been pretty much wasted, since the entire crew would have been both eating and sleeping in pretty much the same area as the cows and pigs.

The East Indiaman Gotheborg III under sail

This was maybe the most visionary and important paintings that was made for the project. For the first time we had a picture we could call our own that could show what the ship we had actually started to build would look like when she sailed. On the painting the hull appear lower then she actually turned out to be, which might be historically correct. Since no actual blueprints of the original Gotheborg (built 1738) existed was the ships builders forced to look for slightly later ships models as drawn by Chapman..

This painting was featured on the cover of the GÖTHEBORGSPOSTEN's August 1996. This 16-page newspaper, basically written by me, was printed and distributed in 360,000 copies alongside the regular local Göteborgs-Posten (GP) newspaper. At this time, GP was one of the project's most significant sponsors, considering the value of our access to virtually unlimited advertising space in this the largest and widely-circulated local newspaper.

The photographs were taken by Sten Zachrisson, with whom I traveled for a week to capture all the necessary images for the magazine.

This exposure significantly boosted the project's popularity in Gothenburg, leading to what could be described as a 'ship craze'. Everybody felt they were part of reviving a brilliantly successful part of our trade and shipbuilding history. For instance, mentioning that you were part of the 'project' and needed to go to the 'shipyard' would often result in a free taxi ride. A kindness I personally experienced from a driver who was unaware of my identity. The community's commitment and volunteer work towards this seemingly impossible endeavor had won the hearts of everybody, young - who wanted to sail, and the old hands - who remembered the old Gothenburg Eriksbergs shipyard with tears in their eyes. This all prompted widespread support.

However, while the enthusiasm was high, major sponsors were still cautious, with only a few offering support, mostly in the form of products.

At this time, Eriksbergs Förvaltnings AB had provided the prime location for the shipyard. Most of the labor force involved in the ship's construction was financed by Länsarbetsnämnden as part of an unemployment relief project, or by us. All monetary funds were raised or donated by the 'Friends' organization and some modest contributions from the community. Project management, meaning me and a few more, was volunteered. Material gifts and minor donations started to come in, at an increasing rate thanks to sponsors events held at the shipyard.

Cooking on board

Painting based on a reconstruction drawing for "Jan-Erik Nilsson: Food on-board Swedish East Indiamen (MS)".

The ship's pantry was located near the fore of the ship so that the smoke that came out from the fire would sweep out forward from the ship. Actually, since there are not one single original Swedish East Indiaman preserved anywhere it was a bit hard to know how it actually would have looked. This reconstruction painting with two fires, one for the common crew and one for the officers appears reasonable believable. This area on board is in general not much noticed and if the fireplaces ever appear in any excavations, it is usually in the form of a pile of bricks.

Table setting around 1745

Painting based on a reconstruction drawing for "Jan-Erik Nilsson: Food on-board Swedish East Indiamen (MS)".

"Osbeck's Punch" served on Board

Painting based on a reconstruction drawing for "Jan-Erik Nilsson: Food on-board Swedish East Indiamen (MS)".

Dining at the "First Table" on board

Reconstruction painting and intended book cover for "Jan-Erik Nilsson: Food on-board Swedish East Indiamen (MS)".

When looking at this painting it is hard to remember that at the time of Lars' painting this picture, there were barely a keel stretched at the shipyard area and that there were nothing like a ship to look at. Still this painting came out very close to reality as the real ship turned out.

Cross-section of the Gotheborg III (preliminary plan)

Acrylic on canvas. Painted for the Gotheborg III magazine as a basis for a sponsoring effort 'component sale' that aimed at asking sponsors to pay for one item at a time from one single ship's iron nail and upwards.

At the time of this painting not much was settled on how the interior eventually would look. The most solid document we had at this time was a paper by Eric Lincoln, (Maskinsystem ombord Ostindiefararen Götheborg III. Examensarbete omfattande 4 p. Inst. för maskinteknik, Ing. o Sjöbefälsskolan vid Chalmers Tekniska Högskola 1994) a maritime engineer at that time studying at CTH and one of the participants in the original project Managing Committee. That paper outlined his thoughts on how to carefully modernize an old ship construction towards something that could actually be sailed. I belive that it was Eric that finally killed my dream of having live cattle onboard, something that later generations of people who have actually sailed with our ship has all reasons to be grateful for.

DRAWINGS

The following drawings was commissioned by Jan-Erik Nilsson as illustrations to his book (MS) on the food on board and the culinary influences that might still be traceable in today's food. The research was based on provision lists and all available references that was found in extant diaries from the actual voyages to China and back during the 18th century.

The diaries offered references to different situations along the travel route that Lars Gills agreed upon to illustrate. Most of the references came from Jacob Wallenberg, Min Son på Galejan, 1767-68.

Värdshuset Klippan

"Jösse, pudding and kapun"

Illustration by: Lars Gillis.

On board, awaiting good winds for departure. Gothenburg harbor outside of Klippan.

"Without alcohol and Danish fur coats we would most certainly have frozen to death". Illustration by: Lars Gillis.

Typically, the ships were outfitted during the winter months and set sail for China early in the year, aligning their journey with the monsoon winds near the equator. Occasionally the weather was so cold that the river froze, trapping the ships in ice. To embark, they had to be towed through a channel sawed up in the ice to reach open water. This illustrates a scenario aboard the East Indiaman 'Finland', as recounted by Jacob Wallenberg in 1769.

Live provisions

Aboard the ship, a large number of live animals were brought to provide fresh food, primarily for the officers and company officials at the 'first table'. These individuals, who paid for their provisions out of their own pockets, had the liberty to bring anything they desired. Depending on their typically excellent personal economy, they often brought considerable quantities of gourmet food and wines. These provisions were loaded before departure and, as opportunities arose, further supplemented along the route. More wine and fresh food and livestock was typically brought onboard in Cadiz.

Involuntary stopover in Norway

During one memorial voyage with 'Finland', the ships once needed to make a stop over in Norway. The crew fed on crows and what they could hunt, at one occasion they even shot an eagel. The cadets were overjoyed for being able to have fresh milk (this might be a straight face joke in the diary which certainly was circulated during the voyage). The officials dined with an old local whose cooking made them bring ashore their own chef to take over the cooking. (source: Wallenberg, 1769)

.

Eating on board

The organization of the dining was strictly hierarchical both in what food that was served, drinks and actual seating.

Ship's pantry

How ship's pantries actually looked are very little known. This drawing is based on a cross section of an East Indiaman, by Röding, published 1796.

Toppling of Turtles at Ascension

Huge sea turtles offered a welcome change in diet on the way home. To catch them was easy; they were just toppled upside down before they could swim out to sea again. In this manner several dozen could be caught in a short time. They were then kept alive onboard by pouring water on them and for one month they could have fresh turtle meat every second day. In 1779 for example, 40 turtles was caught in this way.

Fresh fruit was bought at Java

During many voyages, the Java Straits near Batavia, present-day Jakarta, were during the earlier voyages often the first stop after Cadiz. The Javanese would row out to the ships in their prahus, offering fresh fruits, coconuts, and souvenir pets like parrots and monkeys in exchange for small coins and iron items. The fresh fruits were popular for combating scurvy and were believed to help 'fasten their teeth.' However, this unusual diet often caused dramatic digestive problems among the sailors, to the extent that it 'threatened to bring out the intestines together with it,' as Wallenberg described in 1769.

Candied fruit and sugar glazed bakeries in Canton

In 1804-05 the rules for foreigners visiting Canton had softened up and the 13 year old Erik Marchander was allowed to explore the city alone, being treated most friendly by the locals. (Nilsson 1992, p 34, MS)