To help us see what it could have looked like onboard an 18th century Swedish East Indiaman we have the diary of the Ships' priest Jacob Wallenberg who in 1769 left us his impression from a visit onboard the East Indiaman Finland. This gives us an idea of how it could possibly have looked onboard the Gotheborg a few decades earlier. If something, Gotheborg was even smaller.

Furthermost aft Wallenberg tells us, were the officials' cabins and the medicine chest, which also doubled as pulpit for the priest on Sundays. From there on, along the larboard corridor came the deckhand's' hammocks, the second table where 'better food was eaten' and then a smaller table where the cadets (mid-shipmen) 'had their peas'. On the right side stood some fifty sheep and on the other side, goats, pigs and a cow from Hisingen whose calf had already 'ventured into eternity'. From the cow, they got milk. Further forward was the smoky kitchen, where the foremost hearth was for the table of the masters and in a huge copper bucket, all the rations were boiled for the crew. Immediately in front of this was the galleon, the 'bathroom' for the 150 strong crew. The starboard corridor led around three oxen, the anchor rope and 'there among the chests were the mid-shipmen and the carpenter'. Somewhere around there, the story is interrupted as the stench forces Wallenberg up on deck again. (Wallenberg, Jacob. Min son på galejan, 1769).

The last voyage was a journey full of hardships one surviving member of the crew wrote. When the Gotheborg departed, it carried a crew of 141, in addition 3 boys had stowed away and were discovered far out at sea. When the Gotheborg was cleared in Batavia 10th January 1744, it was noted that 130 men were onboard which accords well with the number of deaths that had occurred up to then (according to the roll of Holmertz). One of the Gotheborg's own seamen, jumped shipped at Batavia while 7 deserters of various nationalities were found onboard as stowaways when she left Batavia on 28 May 1744. After that date, another 17 names were added to the list, evidently recruited or boarding the ship on later occasions.

Some sailors had traveled long to get away from their poverty stricken farms. Others were noblemen's sons who did this voyage in view of a sailor career / seafarer's career. On board was found the ship's captain, a priest and supra cargoists (cargo advisors??) supracargoesse super cargo asses?, all with different backgrounds.

A large part of the crew came from the three ships Stockholm, Riddarhuset and Fredricus Rex Sueciae. All 3 had come home on the 18th October 1742. Sailors who were sailing to East India or China were somewhat of a working group of themselves. The economic conditions were generous. For one thing, besides salary, all sailors had the possibility of bringing home merchandise of their own to sell or give away. A common sailor could with some luck, after a couple of trips, retire as a wealthy man.

The usual stay on land was around 6 months, but before half the time had gone, most of them were as poor as before they had left, some even taking an advance on their allowance / salary for the next trip and spent that too. The long time of absence must have placed a restriction on their social lives and which friends remained when they were at home. The risks / threat for life and health was considerably large even if the alternative could be 10 times worse. The mortality in sicknesses within the Swedish maritime navy for example, was much higher than on the East Indiaman.

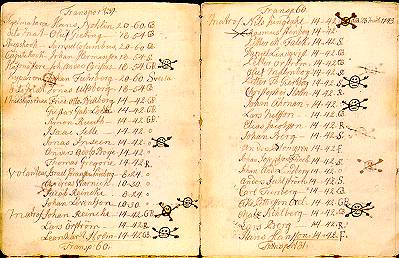

Of the 104 people who were onboard from the outset and who are included in the preserved portion of Holmertz roll, 21 died during the voyage. In addition, 2 of the 25 men added later were noted as deceased and 3 more were struck from the list, possibly deserting. Since some of the 40 men probably missing from Holmertz roll may well have died too, the number of death can be put at about 20% of all participating in the expedition. This high figure shows to tell about many hardships on this journey. In the shipwreck however, it seems that none lost their life.

If you as a sailor, arrived at the city of Gothenburg, it wasn't that easy getting into the city. At this time, the city was actually a fortress with a population of 12,700 individuals and 2,200 military personnel with families. If you came to Gothenburg by land, it was quite possible that you needed to lodge outside the city since the city gates would've been closed and would've opened only the next morning. The road to the city was worn, muddy and in poor condition. Well inside the city, one usually did not dare go out at night, for fear of being stabbed by some drunken soldier walking about in the dark, waving his sword. Street lights were non-existent then.

As late as 1721, a huge fire had left practically the whole city south of the harbor in ashes. But it was now built again with almost only wooden houses. Everybody did agree that stone houses were better but the foundations for a stone house were simply too costly.

To sign up for duty, one would have needed to somehow contact the East India Company. If you were some of the officials, you might have met up with Niclas Sahlgren, who at this time, lived at the current Norra Hamngatan 6.

In 1738, Magnus Lagerström was hired as treasurer and secretary. With his military background, it was he who kept track of all financial and practical issues. His office was most likely at the warehouse and the "accounting house" located west of the German Church today. This was the East India Company's first magazine built in 1745, where the historical museum of Gothenburg is today.

Thanks to that this roll is still existing, we have had access to a part of the roll (perhaps the whole?). The roll of Peter Holmertz is for 101 persons plus 3 small boys who had snuck onboard in Gothenburg. The roll however seems to have been missing 2 pages with an additional 40 names. So they had possibly sailed with a crew of 141.

The highest in command was Anders Taubeltou (August Tabuteau), the premier supercargo'. This was the highest in command on board. His last trip was to Bengal with Fredericus Rex Svecia. He, as so many others, came home as late as the 18th October the year before. One single document was a note, dated 26 April 1746 from "H. Koenig Campbell & Co" with a requirement for the council that "Mr. Premier Supercargo, should sign his agreement / oath / declaration given under oath, the reason for the foundering". After which we will never hear about August Tabuteau again.