Dish brought up by James Keiller and Carl Lyon during their salvage operation 1906-07. A large part of the cargo was sold by James Keiller together with a certificate telling about the background. Souvenirs like this occasionally occurs in the antiques trade. Photo © JE Nilsson, Coll. 2023

Already in 1976, I had started to become seriously interested in Chinese porcelain. Fresh out of school I invested my first paycheck in a large 18th century serving dish, bought a few books and later next day, went back and bought a vase I still have. I was amazed to discover that just a few blocks from where I lived, there was the former head office of the 18th-century Swedish East India Company (1731-1813). Moreover, not only was the head office building still standing, it was now the Historical Museum and they had lots of porcelain and other artifacts from the time of the East India company. Somehow it felt like the time had stood still when you walked around in there among the old auction room and storage vaults, still numbered.

My interest grew as I realized that a fully laden Swedish East Indiaman had sunk just outside of the Gothenburg harbor and was partially brought up as recently as 1906-07. A significant quantity of porcelain had been recovered, some of which was sitting in a large cabinet in the Museum.

This discovery made me a frequent visitor at the Museum. I also found out about the mid-19th-century salvage operations by Mr. James W. Bourn (1864-65), Johan Kjellberg (1866), Captain M. Lampa and Mr. Chudley, Birmingham, (1875-76). Further information, including a handwritten excavation report signed James Keiller (1907) were available in the archives of the Museum of Maritime History in Gothenburg, complemented by a substantial collection of private belongings of the crew.

Eventually, I began delving into the history of the Swedish East India Company (1731-1813), and the mystery that seemed to shroud the sinking of the Götheborg in 1745. By this time, I had also started to find Chinese porcelain among the many antiques shops in the city, occasionally finding pieces that must have come from the wreck.

Gothenburg Historical Museum celebrates 250 years anniversary of the founding of the Swedish East India Company (1731-1813). Naturally well featured in the exhibition was porcelain from the Gotheborg that was brought up and donated by James Keiller in 1906. The sign board also offers an exhibition of a model of the 'East Indiaman Gotheborg' and Chinese armorial porcelain from the Strokirk collection.

Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 1981.

In 1981, I was invited to participate in the planning of the Gothenburg Historical Museum's celebration of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the Swedish East India Company, housed in the former head office of the Company, at Norra Hamngatan, which made it all the more interesting. The museum director, Dr. Ingmar Hasselgreen, specialized in architecture and was not particularly that much into porcelain, which meant that this aspect was pretty much left to me. Some porcelain for the exhibition was brought from the museum's affiliate, Lilla Änggården. One evening we went there together to check out a blue and white service that was kept there. I am not sure if it made it into the exhibition since I think it might have been a fairly ordinary willow pattern from possibly after the SOIC company period.

Model of a 18th century East Indiaman being built - aft towards the water - exhibited at the Swedish East India Company 250 year anniversary at the Gothenburg Historical Museum in 1981. Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 1981.

Part of the most interesting exhibits in the museum to me, was the porcelain donated to the Museum in 1919 (GM:7443) by James Keiller who in 1906 to 1907 had thoroughly salvaged what he felt was worth salvaging from the East Indiaman Götheborg.

When collecting anything, it is normal that you also want to know more about it. It appeared to me as if, on the muddy bottom of the Göta River, there rested a fantastically exciting treasure that could help me understand the life and motivations of the 18th-century people who brought this exciting porcelain back home to Sweden in the first place.

It was also obvious that this cargo could prove an invaluable help towards the dating of otherwise un-datable Chinese export porcelain, still available in droves in Swedish antique shops. One thing to remember is that this happened in the early 1980s, which was much before people like Michael Hatcher had started to pick up whole porcelain cargoes in the South East Asian waters.

One question that intrigued me, and to which I could not find an answer, was how come the Gotheborg sank so close to home in the first place? It just must have left some kind of impression in the literature, somewhere?

The local Gothenburg lore was full of memories and myths from the time of the mysterious sinking of the Swedish East Indiaman Gotheborg 240 years earlier. If you had asked anyone at that time, everybody was certain that there had been something funny going on, and that there must have been some monkey business involved. But nobody could tell what. It was just 'felt' that something was wrong

I looked everywhere for answers.

The Regional Archive (Landsarkivet) had a large collection of documents, but nothing that answered this simple question. The Museum of Maritime History in Gothenburg had some documents too, many of which were related to the salvage operation by James Keiller and Carl Lyon around 1906. The one sentence "due to the shortcomings of the pilot" that appeared in Sven T Kjellberg's (1972) book about the Swedish East India Company, remained the only clue there was. Eventually I even find this actual line - a tiny line in a small neat handwriting - in the Ledger A of the SOIC at the Regional Archive (Landsarkivet) in Göteborg. But besides this, all else remained in infuriating darkness.

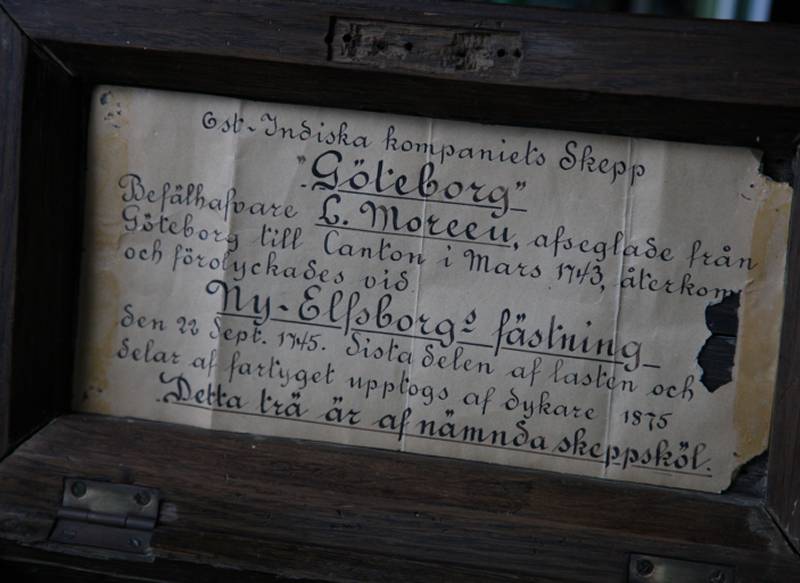

In the collection of the Historical Museum of Gothenburg, there were also some artifacts that were said to have been made from blackened oak from the hull of the original Gotheborg. On these items, there occasionally occurred small handwritten messages glued or stapled onto them, suggesting that there had been something not quite regular with this sinking. The word used was "underslef," meaning fraud or embezzlement - literally that you deliver less than you charge for. However, nowhere was there any substantial information to be found. Other sources talked about hidden compartments in the hull that had been used for smuggling silk or porcelain but failed to connect the dots to anything like a coherent explanation.

The artifacts could look like this, this box measures 12 times 7 times 3.5 inches (30x18x9 cm) and is "made from blackened oak from the keel" of the East Indiaman Götheborg. The Historical Museum had a chair and a mirror frame inscribed in a similar way. Maybe one particular carpenter had got his hands on the keel and was specializing on this kind of memorabilia as long as the wood lasted?

In this process, I had started to track down and read every single book that could possibly mention this "accident." My hope was that somewhere in a fleeting observation, there would be a recorded contemporary explanation about what had happened, or at least something. Most hope I had, were in contemporary newspapers or travelogues, or published diaries that covered the period, but nothing. One of the reasons was of course that at this time, there were hardly any newspapers, in the first place.

The result of this endeavor is available here as a bibliography, listing 553 titles of books and documents.

By now, I had started to become convinced that there must have been something unusual and irregular going on here. I found it hard to believe that a financial loss of this magnitude, involving both ship and cargo, could have occurred within sight of the home harbor without leaving any clear explanation in any document. With a crew of 200 and a city population of about 5,000, there must have been few families that did not have a relative or neighbor on board. Why was there no explanation?

Then suddenly one reference appeared. It said that "in 1745 the captain Moreen himself was to come down to the City Magistrate to, with 'hand on pen,' sign an explanation to what had transpired." This was good news, but then again, nowhere in the archives could this specific document be found.[footnoot reference to the document]

Anders and Berit Wästfelt have just arrived back home from Eilat and are setting up Marinarkeologiska Sällskapet, Göteborgskretsen (MASG). Anders start looking around for an interesting enough wreck site that could be used for teaching marine archaeological competence and diving skills.

A few years earlier Anders and Berit Wästfelt had come back from Eilat in Israel, where they had successfully run a diving school. Well back in Sweden, he had founded Marinarkeologiska Sällskapet, Göteborgskretsen (MASG) and was looking for an interesting enough wreck site that could be used for teaching marine archaeological competence and diving skills.

The Western Swedish Archipelago offers many possible wreck sites from the Viking age and onwards.

In December 1984 as luck would have it he received a telephone call from the marine archaeological author Catharina Ingelman-Sundberg who was researching famous Swedish ship wrecks for a book she was putting together, and wanted to know if Anders knew anything about the East Indiaman Götheborg that obviously had foundered and sunk at Nya Elfsborg, basically just outside of the Gothenburg harbor.

Then, as fate would have it, the antiques dealer Björn Gremner at AntikWest AB, introduced me to "a diver who had been down to the ship you are so interested in," as Björn put it. This was around the time of Christmas in 1984. And yes, I was interested in meeting with him. His name was Anders Wästfelt, and he appeared with a box of shards and some wooden sticks. No doubt, these were porcelain shards and wood from the tea and porcelain chests of the lost East Indiaman Gotheborg. This, nobody had seen for a very long time.

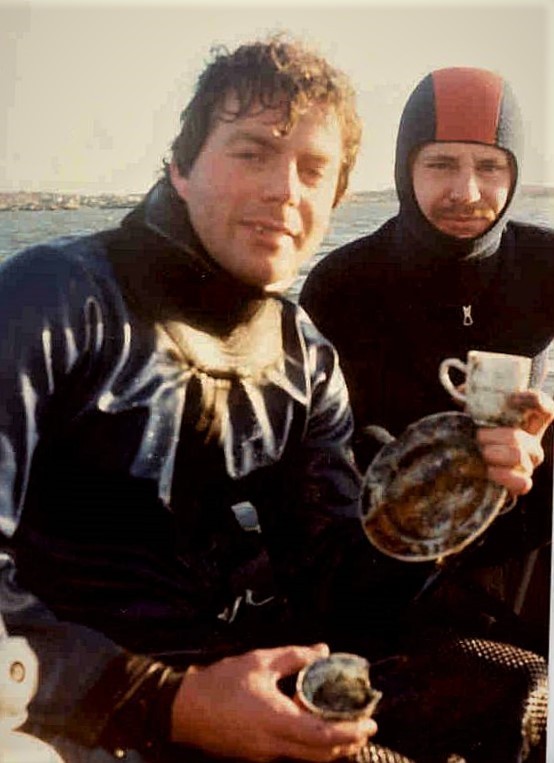

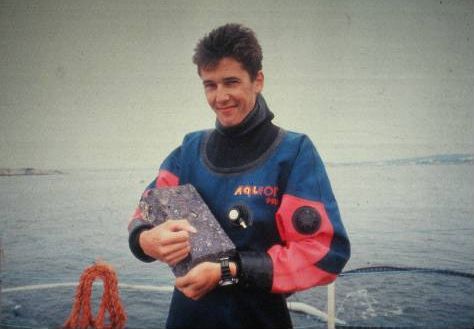

First dive in December 1984. Anders Wästfelt brings three diving friends to Hunnebådan in search of any remnants of the wreck of the original foundered East Indiaman Gotheborg. They are successful. Anders Lyckdal (left) and Anders Lindvall (right) coming up with the first finds. The wreck site of the lost East Indiaman Gotheborg had been found.

Photo: Anders Wästfelt, 1984

At the bottom Anders Wästfelt and his friends found an area large as several foot ball fields completely strewn over with porcelain shards and all kinds of wooden artefacts. It was no doubt that this was the wreck site, but there were no trace of the hull. What had happened?

Photo: Anders Wästfelt, 1984

From then on we met regularly. Anders and his divers cum maritime archaeologists team did a lot of ground breaking research as the excavation progressed. The public interest in the Swedish 18th century as a period of peace, trade, science and general progress was very much promoted. Even academia started to change focus from the Great Power period of the 17th century towards the scientific and culturally more interesting 18th century.

The underwater excavation which was followed via extensive publicity, thousands of lectures and a large number of international exhibitions went on during 1986-1992 and created the goodwill and public interest that would later fuel the ship building project.

In 1986 the Wästfelt excavation of the Gotheborg is commenced with its first diving season. Knowledge of the main proportions, the rig, the armaments, and other details of the ship is starting to be collected. Two first test trenches are dug. Large amounts of Chinese porcelain shards, remnants of broken tea crates, larger ship's construction parts are found.

The excavation was run as publicly and openly as possible. It caught the imagination and sympathy of wide swaths of people, from international to local governments, to the Swedish industry, and our tourist and business community, not to mention the public who all loved it.

The Friends of the East Indiaman Götheborg Organization is established in February to support the excavation project. Erik Wettergren becomes its first Chairman.

During the excavation the first complete and unbroken porcelain items are found. Different types of ammunition is also found together with personal belongings from the crew. Complete sides of tea crates are found.

During the excavation period innumerable events and lectures was held to popularize the excavation of the East Indiaman and its results.

Details from the ships stern are identified.

The first complete bundle of intact porcelain plates are found which gives a first clue about what the the bundles listed in the cargo list could have looked like. Two large sections of the ships aft are lifted up.

Mud and findings from the excavation area down at the bottom are pumped up to the diving platform, anchored over the wreck site, flushed over a fine meshed sieve. Anything interesting looking are kept and sorted by its main categories. The sieve is fine enough to catch pepper corns and even remnants of diverse insects from being flushed back out into the sea. Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 1990

The original location of the wreck is found and decided with certainty. The fact that the ship in its construction had been inspired by the British could be noticed by the fact that the ship had been equipped with an extra 'loose' keel, to improve its sailing ability.

One of the 6,056 bars of 'Tutanego' the ship had originally carried from China.

It could finally be confirmed that this elusive metal was nothing but plain zinc.

One of the 6,056 bars of 'Tutanego' the ship had originally carried from China was found. The total weight could be decided to 21.6 kg which with a high degree of certainty could confirm that the Bill of Lading was correctly listing c. 130 tons.

Last season of actual excavations. The area close to the ship is investigated. The entire excavation area is covered with gravel to indicate for future investigations which area has been disturbed. Finds that could not be preserved are put back and filled over. Remaining excavation equipment was taken up and put in storage at New Elfsborg Fortress.

During the year three international exhibitions are undertaken to promote the finds, the ship and prepare the ground for a possible continuation.

In 1992 the findings from the excavation of the East Indiaman Gothenburg is exhibited in Shanghai.

A 44-meter-long banner, displayed on the facade, announced the exhibition, which eventually attracted almost 30,000 visitors. At this moment, with the exhibition nearly ready to open, we went out to see the banner being hoisted.

Anders Wästfelt, to the right. Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, Shanghai, 1992.

The findings from the excavation of the East Indiaman Gothenburg is exhibited in Shanghai, organized by Anders Wästfelt and the Swedish Consul General Bengt Johansson, in Shanghai. The exhibition is much published in Chinese media and is visited by large Swedish delegations, mostly from those already established in Shanghai.

During the last few years of the excavation phase, Anders Wästfelt began to conclude his hundreds of lectures and presentations with the words - and now we are going to build up the East Indiaman Gotheborg again, and sail her to China and back, again, but this time, we are going to make it all the way back into the harbour, and not hit Hunnebådan and sink again, alternatively - and start the trade again and we will all become very rich, depending on the crowd.

I still don't understand why that brought laughter and applauds. We were quite serious.

You can't really say it was only Anders' idea to try to build her all up again. Everybody involved was thinking about what she had looked like, and felt like to sail. I think there you have it. But it was he and a small group of very serious professionals who accepted the challenge and pushed it through to completion. Admittedly my first thought had been 'I wonder if we could pick up all that old wood lying down there, in the water, to see if we could piece her back up together again'. But that was of course impossible. Too much was missing and what was left was in a miserable condition.

But what if we could figure out what she had looked like and build a replica? Really? It was impossible to let go of that idea.