Back to Gotheborg.com Home Page

Back to Gotheborg.com Home Page

The former main building of the Swedish East India Company still occupies the best piece

of land in the City of Gothenburg despite it lost its business purpose already in the 1813.

Photo: Jan-Erik Nilsson, 2005

Goods from the Orient have always been regarded as exclusive and exciting in Europe. Since the days of the Silk Road, European traders have conducted trade primarily with China. What attracted them were goods like silk, spices, porcelain and tea, which could be sold at a good profit in the domestic market.

'The Silk Road' was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BC until the mid-15th century.

It began with the Han dynasty's expansion into Central Asia around 114 BC. It played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the East and West.

The first trade contact between the East and West was via a complex land route over central Asia that facilitated cultural, commercial, and technological exchanges from as early as the 2nd century BCE. It was called 'the Silk Road' from the highly lucrative trade of silk textiles that were produced almost exclusively in China.

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) negotiated under the auspices of the Pope, divided the world between Portugal and Spain. This treaty allowed Portugal to claim eastern territories including parts of Africa, Asia, and Brazil, while Spain received rights to colonizing the western. Therefore, it was natural for them to approach China from their respective directions.

Portugal: The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish direct maritime trade with China. This was achieved under the leadership of explorers like Vasco da Gama and Afonso de Albuquerque in the early 16th century. The Portuguese established a permanent settlement in Macau in 1557, which became a major trading port and a gateway for European merchants and missionaries to China.

Spain: While the Spanish primarily focused on the Americas and the Philippines, they also indirectly reached China through the Manila Galleon trade. The Spanish established Manila as a colonial capital in the Philippines in 1571, which then became the endpoint of the lucrative Manila Galleon trade route. Through this route, they indirectly engaged in trade with China by exchanging American silver for Chinese goods like silk and porcelain.

Following the Treaty, the early 16th century saw Portugal and Spain effectively dividing the world's newly discovered lands between themselves. This colonial expansion led to significant cultural changes, conflicts, and the spread of Christianity in the colonized regions.

However, they could not maintain a world monopoly on this trade for long. By the end of the 16th century, the English and Dutch began to compete for the trade. England formed its East India Company in 1600 and Holland shortly thereafter in 1602. Both companies were granted charters for this trade for 15 and 21 years, respectively. Several countries followed suit and formed East India Companies, such as Denmark in 1616 and France in 1664.

This marked the beginning of intense competition among European powers in the East and outright wars were waged between the companies both in India and Indonesia. As a result of these wars, England eventually became dominant in India and Holland in Indonesia, which has shaped the history of these countries into our time.

Sweden also had made an early attempt to start a company that would trade with Asia, Africa, and America. In 1626, Gustav II Adolf granted a 12-year charter to a Dutch merchant which is not specifically named in widely available historical records. However, the attempt failed due to difficulties in raising funds and the turbulent situation in Europe. At the end of the 1660s, another attempt was made, this time by a Swedish merchant, but it failed for the same reasons.

Perhaps more spectacular was the attempt made in 1718 by a pirate named Morgan, based in Madagascar, who promised to send 60 richly laden ships to Gothenburg if they were allowed to settle there and conduct East Indian trade under the Swedish flag. However, this attempt also failed due to the death of Charles XII and the uncertain conditions that arose when the great power of Sweden collapsed. The story is somewhat ambiguous since there were actually a Sir Henry Morgan who was indeed a notable figure in the 17th century, known for his exploits as a privateer and his role in the Caribbean, particularly around Jamaica and the Spanish Main. His actions often straddled the line between sanctioned privateering and outright piracy. But his career as a privateer occurred earlier (in the mid-to-late 17th century) than the Swedish trade attempt in 1718. However, following his privateering career, Morgan was knighted by King Charles II of England and eventually came to serve as the Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica.

About this time, in the early 18th century, the Swedish economy was in ruins after almost a hundred years of war with neighboring countries. Sweden needed a new beginning. Peaceful contacts with Europe and the rest of the world were intensified. The city of Gothenburg on the west coast of Sweden was ideally located for an important role. The successful English and Dutch East India companies already trading were closely studied and the decision was made to develop international trade with China.

Finally a successful attempt to start a Swedish East India company was made in 1729 by the merchant and commissioner Henrik König & Co. The company was seen as a means to enhance Sweden's economy. The importation of Asian goods without middlemen would increase profits and foster economic growth. Foreigners with capital would move in, shipbuilding would be encouraged, and the youth would be trained as seafarers. This could contribute to the development of Sweden as a nation. On June 14, 1731 His Royal Majesty granted Henrik König & CO a Royal Charter for 15 years to peacefully trade in the East Indies and other places located east of the Cape of Good Hope. The most successful business was made with China, through the port city of Guangzhou (Canton).

The government hastened to inform the other maritime powers of its involvement in the East India trade and requested permission to call at their ports along the way for repairs and provisioning. The responses clearly showed their hostile attitude towards the new company. France stated in its response that Sweden appeared to be aligning themselves with the Vienna Alliance, which was hostile to France. The Netherlands argued that a new company would worsen conditions for its own trade, and in England, the mood was such that they did not even dare to raise the question.

During the years between 1731-1813 The Swedish East India Company (Svenska Ostindiska Compagniet) made over 130 trips between Gothenburg and China of which some also hit India.

The Scot Colin Campbell of Argyll, one of the founders of the Swedish East India Company. The China Trade was a risky business. Taxes, tributes and bribes, often hard to distinguish were rife. Storms, pirates, diseases and rival traders were constant threats during the two-year round trip voyage from Europe.

The launch of 'Fredricus Rex Suecia' marked the beginning of Sweden's active participation in the East India trade. The ship, initially designed for Mediterranean trade, was repurposed for longer voyages to the East Indies. Naming it after the Swedish king underscored the national backing and ambitions behind the venture. The Fredricus sailed from Gothenburg on May 7, 1732, with the well-merited premier captain of the Fleet, Georg Herman Trolle, as commander, and Colin Campbell as First Supercargo and the actual commander of the voyage 'Deciding to put not only his money at stake but his own life, to ensure the success of the trip (Campbell, C. Diary) .

The journey departed from the port in Gothenburg, usually with a stop in Cadiz on Spain’s west coast, they rounded the Cape of Good Hope and continued towards the South China Sea to reach the Pearl River and finally the goal - Canton.

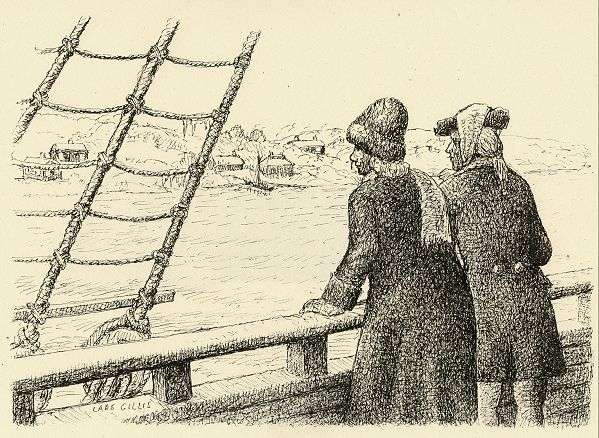

Usually the ships were fitted out during the winter period and sent off to China in the fist months of the coming years to fit better with the monsoon winds of the South China Sea. Occasionally the weather was so cold that the ships froze stuck in the river and needed to be pulled out to clear water through a sawed up channel of ice. The illustration shows a situation on board the East Indiaman 'Finland', as described by Jacob Wallenberg in 1769. Illustration by: Lars Gillis.

When the ship returned to Gothenburg and the return cargo was sold, it was clear that the expedition had been a success. The Board of Directors reported that the auction of the cargo had brought in 900,000 Daler Smt, and that a dividend of 75% on the invested capital could be distributed.

The Swedish East India Company's successful trips to China created a passion and a taste for Chinese art and philosophy during the 18th century.

In the early 18th century, the collecting of Japanese and Chinese porcelain became an obsession among the European aristocracy. Separate rooms and castles were built to display the collections. One of the most devoted was Alexander the Strong of Saxony who in the process actually were instrumental in discovering the secret of porcelain making himself.

There were also critique towards the newly established company. Fears was raised that the country would be 'flooded with unnecessary luxury items'. It was feared that such a quantity of cheap and poor-quality silk goods would be imported that 'even servant girls would not want to dress in anything else' and that vanity would overwhelm women to the point that they would 'not want to wear a dress for more than a few months'. Others argued that Sweden would be depleted of its natural resources, and after a few years, nothing would remain but worn silk fabrics, broken porcelain, and drunk tea (Linneaus. C. v). However, many of the goods brought home by the ships were in turn exported to countries in Europe, which meant that capital flowed into Sweden. Goods manufactured in Sweden could be exported with the ships, benefiting Swedish industry. Eventually, the advantages silenced the opposition. Recent research (Rönnbäck, K., & Müller, L. (2020). ) have confirmed what was previously only felt, that the transshipping of primarily tea was much more beneficial and played a much larger importance for the Swedish Economy than previously thought.

During the most extensive period of the Company's operations, the company carried annually between 600 and 1200 tons of tea from Asia to Europe, accounting for about 15% the European tea imports from China. This was less than what the English East India Company imported, but about the same as the Dutch, Danish, and French annual tea imports. Considering the fact that Chinese tea, just behind Indian cotton, was the most important commodity in Euro-Asian trade, the Swedish Company was a major transnational trader. The research show that the success of the company was not based on monopolized domestic market in Sweden but was rather based on re-exports to other countries in Europe. The Swedish East India trade made up an important share of the Swedish economy during a long part of the eighteenth century.

City of Gothenburg in the early 17th century. Detail, as seen from the well known viewing spot at Danska Vägen.

Behind the church and houses we can see ships at the Göta River. Top left is New Elfsborg Fortress inserted but it is not actually visible from this spot; it is further out.

Curiosity about the world was great. Some of Carl Linnaeus' disciples went on the trips to conduct studies on flora and fauna, Chinese science, art and culture. They observed and gathered information that could be of use in Sweden for research and development of trade and other things.

The seafarers first encounter after passing the Portuguese colony Macau was the Pearl River. About where the Pearl River started to become narrow they encountered a passage that was called Boca Tigris - The Tiger's mouth. Further up the river was the island of Whampoa near which the Western ships laid anchor during the trading season. The last journey up to Canton itself was made in smaller vessels. The Pearl River views were in itself popular motives on paintings and porcelain and numerous views were made by anonymous artists in studios in Canton and exported to Europe.

Due to centuries of bad experiences the Chinese rightfully regarded all foreigners with suspicion whatever the pretext. Contacts with the "Foreign Devils" were severely restricted. Trading was allowed only in Canton under the supervision of especially appointed Chinese "Hong" merchants. Foreign merchants were initially not permitted to stay permanently in China and could only visit their warehouses during the trading season.

Once trading was finished, the cargo was brought on board - porcelain in bundles, tubs and wooden boxes cushioned with rice paddy or marketable goods such as galangal, pepper, rice, sago, or tea, at the bottom for ballast, followed by chests of tea and finally the precious silks and spices.

To trade with the Chinese was difficult both due to the geographical distance as well as the cultural differences. To keep things simple the Swedes brought pure silver cash coins in the shape of minted Spanish coins. A complicating factor was that Swedish East India Company by Swedish law was forbidden to export Swedish silver coins out of Sweden. Not taking home the export profits in the first place, but making them available against documents in Spain, circumvented this. Often as much as 5 tons of minted silver coins were brought onboard in Cadiz.

When the ships arrived to China tea, porcelain, silk and spices was bought for the silver.

Usually starting from China in the winter with the western trade winds, the cargo was brought back to Sweden to be sold at auction in Gothenburg.

The business gave large profits to both the Swedish and the Chinese merchants and continued during more than 80 years.

During this period the Swedish company built 38 East Indiamen sailing ships and made 132 trips between Sweden and Asia - most of them to Guangzhou (Canton) in China, but some also touching in India. Most went well but sometimes disaster struck as with the East Indiaman Gotheborg in 1745. During the active period all in all eight ships were lost.

Trade painting of the European trade offices, called hongs, in Canton from which the business was run and where the bought in items eventually was stored awaiting transportation to the ships waiting at the Whampoa anchorage a few miles downstream from Canton in the Pearl River.

In its time the SOIC was a very profitable undertaking. The trade created fortunes, industries and promoted cultural exchange, philosophy and scientific research, making Sweden the world leader in several areas. Despite the risks, traders made huge profits for their companies, themselves and their countries. The Chalmers School of Technology and the Sahlgren University Hospital are named after the company directors William Chalmers and Niklas Sahlgren, who donated the founding capital to these today important institutions.

Every winter one or several ships was outfitted and sent out to China or occasionally to India, to try their luck in having a safe passage, obtaining a profitable cargo and bringing this, the ship and its crew safely back to its eagerly awaiting shareholders, investors and loving families.

In general they would leave Gothenburg in January to February and touch the Straits of Java around July to August. From Java to China would take another month. To settle all businesses in Canton and take in the return cargo would take from mid-September to the end of December after which you would leave China immediately after Christmas to be back home after another 7-8 month.

Usually a journey from Sweden to China and back would take from early spring one years to late summer the next, or 17-20 months. If the unfortunate ship was forced to stay at some halfway island to wait for the trade winds of the monsoon periods to change the voyage might take almost one more year, or some 26-31 months.

The voyages were dangerous and by far not all of the crew members came back.

In 1813, the Swedish East India Trade was given up. Tea was no longer profitably enough because of political changes in Europe. Other companies depended on opium trade for their profits, a trade the Swedish company decided to stay out of.