By Frank B. Lentz

A bird's eye view of Jingdezhen showing some of its chimneys

CHINA is a land of literature, art and scholarship. It is also a land of ignorance, superstition and misery. It is the country made famous by the printing-press, mariners’ compass, gunpowder, the Great Wall, tea, silk, jade, paper and ancient porcelain; it is the home of plague, famine, intrigue, flood, graft and corruption.

Conservative of the conservatives, it is also a radical among radicals. One sees in every city ancient, decaying temples, with their oriental systems of religion gradually giving way to the progressive onward march of civilization. Change, change; nothing is permanent in China but change.

Industrially the country is in the same state that Europe was in before the approach of the industrial revolution. It is in the handicraft stage of development; but in cities like Canton, Shanghai, Hankow, Changsha and Tientsin the most modern machinery of the twentieth century is seen in operation every day. This is not China. The real China has yet to learn the value of the machine.

Perhaps the only factor which permits China to combine in a commercial way with the rest of the world is its cheapness of labor. It has been repeated said that the cheapest and most abundant thing in the country is human life. The common man of the farm or of the city is the coolie, properly called "k’u li" or better, "strength". When we reflect that 80 percent of China's vast population is forced to labor hard, barehanded, for a mere physical existence, we can begin to grasp the significance of its industrial situation. No modern inventions; no machines have come to set it free. Like Edwin Markham's "Man with the Hoe", the Chinese worker feels the weight of centuries of toil upon his shoulders.

The economic problem today is traffic and were it not for its natural characteristics of patience, China would be in the throes of a bloody revolution.

The greatest industrial city of China is not one of the treaty ports, where the direct influence of Western progress is constantly felt, but a bustling interior city of Kiangsi Province – Jingdezhen (also King-teh-chen, King-te-chin or Chang-nan-chen). This is the famous porcelain and pottery center of the nation – indeed, it is the original home of the porcelain industry of the world.

There are few cities in America or Europe that are so completely given over to a single industry as this one. Though the methods of production are primitive, the city must still be classed as an industrial center. It was my rare privilege to visit this conservative, but interesting old place and see with my own eyes the fascinating process of pottery-making from beginning to end.

Chinaware! What does the word connote? It is simply a ware made of clay and named for the country that first produced it. Whether it be a green tile from a temple roof, a dish, a vase, or a painted ornament from a wealthy Celestial's home, it all has a traceable connection with Jingdezhen. With the Chinese, Jingdezhen and porcelain are synonymous.

In order to get a fair understanding of the situation, it will first be necessary to let the reader know the location of this place and something of the difficulties in reaching it.

After locating Shanghai on the map of China, one should trace his way up the Yangtze River to Kiukiang, south of which lies Poyang Lake. The quickest and surest way of reaching Jingdezhen is to proceed from Kiukiang to Nanchang, the capital of the province by rail. This trip can be made in a day, barring accidents, though the distance is only 90 miles. In no respect an industrial center, Nanchang has many wonderful porcelain shops, all supplied by the factories of the porcelain city.

In prospect it did not seem a difficult task to cover the distance between Nanchang and Jingdezhen, 120 miles, but in reality the trip required more time than it takes to travel from San Francisco to New York. One must cross the east end of Poyang Lake and then push his way up the North River into the heart of the mountains, to a point not far from the Anhui border.

Traveling by a small and rickety steam launch, which was completely covered with a cargo of human freight, we left Nanchang, passed down the Kan River and out across the lake. It was 8 o'clock on a June morning and the thermometer registered 90 degrees.

We steamed merrily along until noon, when we suddenly struck a mud flat. My heart sank as numerous stories of people stranded for several days in the middle of this vast stretch of shallow water flashed into my mind.

Fortunately, we were running at half speed, and after violently churning up the mud, we were able to back off and strike a new course, sounding our way until we entered the mouth of the river leading to Raochow [Jaochow, today 'Shangrao'], the most important city on the lake.

At Raochow [Jaochow] our house-boat experience began. With the assistance of the water police captain, we at once transferred to a small but comfortable boat. It was not, however, until after nearly an hour's delay, due to the necessity of purchasing some eggs, vegetables and charcoal for the journey, that we started upstream against a swiftly running current, just as the stars came out.

The police captain had been informed by wire of our coming and was waiting for us with a guard. These guards are stationed at intervals along the river in "p’ao Ch’uan" or gunboats, and are supposed to help in the collection of the revenue tax and to protect travelers from bandits.

The single unarmed soldier who was provided for our protection proved very useful in steering the boat while the three boatmen paddled, poled, and pulled our craft up into the higher reaches of the stream.

All night long they worked, now and then singing, first to the water spirits and then to the spirits in the heavens. After an interval of rowing for a mile or more, the boatmen would rest by getting out and taking the boat in tow with a long rope attached to the mast, while the guard sat in the stern at the rudder and kept us away from the shore.

The craft itself was about 40 feet long and was divided into three sections, with space in each for two "p’u kais" or mattresses. In the stern, covered with boards, was a charcoal stove, with an ample supply of rice nearby. The principal articles of food were eggs, rice, fish, several kinds of vegetables, and tea – good, substantial food when one is living in the open. By removing the floor and standing on the bottom of the boat, one could assume an erect position with ease.

Life on a house-boat means an abundance of fresh air and freedom from the ever-present and noisy Chinese crowd. To appreciate its comforts, one must make the boat his dwelling place long enough to grow attached to it.

Late in the afternoon of the second day out from Raochow [Jaochow] we approaching Jingdezhen. I shall never forget the thrill I experienced as I first caught sight of the smoke issuing from the chimneys of score of kilns. Quite an ordinary scene in any Western industrial city, but here, far away from the main routes of travel, in a conservative, interior province of China, it was as striking as it was unusual.

The first view one gets of any Chinese city is likely to be a bold outline of tower or temple, but in Jingdezhen, the first thing that caught our expectant gaze was something entirely different.

The situation of Jingdezhen is perfect, from the Chinese point of view. The city is located between the mouths of two rivers which flow into the North River, one from the east and one from the west. The town is naturally supplied with an abundance of fresh water, the clearness of which still stands out in my mind in vivid contrast to the muddy yellowness of the Yangtze and of Poyang Lake.

Beautiful hills completely surrounded the city, those on the east rising to a height of about two thousand feet. The river banks are dotted with pine and camphor trees, while occasional groves of bamboo in lighter green add a charm and beauty difficult to describe. For the most of my life I have lived among the giant redwoods of northern California, the stateliness and vastness of which have always deeply moved me. In them I saw strength and power. But in the groves and trees of Kiangsi I found a softness and beauty typical of another world – a tropical world.

Jingdezhen ("Town of Scenic Virtue") is one of the four largest towns of China. Technically, it is a town, because it has no wall. In reality it is a busy industrial city of 300,000 people, two-thirds of whom are engaged in manufacture and sale of porcelain. Romantically, it is a city to stir men's souls. Longfellow, in his "Keramos", speaks of it in these words:

"And bird-like, poise on balanced wing

Above the town of King-te-tching,

A burning town, or seeming so, -

Three thousand furnaces that glow

Incessantly, and fill the air

With smoke uprising, gyre on gyre,

And painted by the lurid glare,

Of jets and flashes of red fire."

Historically, it dates back to the Han Dynasty 220 AD, during which period we find the first records of the production of porcelain in China, though earthenware vessels were probably produced some centuries earlier.

Two main streets, about three miles long and conforming to the contour of the river, comprise the principal thoroughfares.

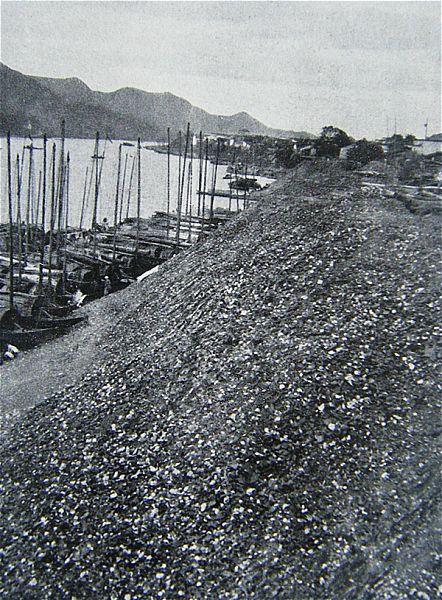

The city is about a mile wide. Furnaces, warehouses, shops and homes are crowded together in a hopeless tangle. Great mounds of chipped and defective porcelain, clay chips, and broken dishes are piled high along the river bank.

In fact, we first noticed these pieces of porcelain in the bed of the stream several miles below the city, washed down by high water. These dumps must be 30 or 40 feet thick. They represent the accumulated off castings of the kilns for centuries. From an eminence to the west I counted 78 big yellow chimneys, this number being about half the smokestacks in the city. It is said that Jingdezhen in her most flourishing days boasted several thousand kilns.

The Potter's mistakes

Great mounds of chipped and defective porcelain and broken dishes are piled high along the river bank at Jingdezhen.

The most unusual feature of the City of Porcelain is its conservatism. "Bu k’ai t’ung" (not open to communications) is heard on every hand. Although China is home to the printing-press, there is not a single newspaper, daily or weekly, published in this city of more than a quarter of a million inhabitants. The reason given for this unprogressive state of affairs is that the magistrates have always opposed the press, on the one hand because they are afraid of its political influence, and on the other because of the financial support that would be involved.

Jingdezhen is devoid of electric lights and telephones. The few rickshaws which now facilitate communications are fighting for existence. While we were in the city a number of workingmen’s guilds petitioned the Chamber of Commerce to abolish the rickshaws on the ground that they interfered with traffic.

There are many indications of progress, however. Christianity is influencing the life of the city through three Protestant churches – the China Inland Mission, the Methodist Episcopal, and the American Protestant Episcopal – and the Catholic church which has been in Jingdezhen for 60 years.

A park located beside a lotus covered lake, is the recent creation of a liberal minded magistrate. Within two years this has developed into a social center, with its industrial museum, restaurant, arbors, open paths and walks. It is the only place in the city where one can get a breath of fresh air.

The Orphan Asylum is an institution that cannot be overlooked. It should be properly named the Abandoned Girl Baby Asylum. Last year 245 girl babies were received by this institution through a small door in a revolving barrel which is located in a niche near the front gate. Later these babies were sent out into the homes of the city to become wives and servants of the well-to-do class.

Jingdezhen has twenty-two schools enrolling about 2,000 pupils of grammar grade age. The Chamber of Commerce is a live organization, housed in a modern foreign-style building headed by a merchant-scholar of much executive ability.

The geographical location of Jingdezhen is not accidental. It became the pottery center of the country centuries ago because of the enormous quantities of excellent clay in the district around Poyang Lake. More than a dozen kinds of excellent clay are found in the neighborhood of the lake.

The chief places from which the hard paste comes are Nan K’an, Yu Kan, Tung Kengn and C’hi Men. At Ch’i Men, which is just across the border in Anhui Province, there is a whole mountain of fine white clay.

Two very descriptive words are used by the Chinese in referring to the composition of porcelain – "c’hi ku", or porcelain bone and "c’hi ro", or porcelain flesh. The former gives strength and brittleness to a vase or bowl, while the latter adds resiliency and toughness. Unless these clays are mixed in the right proportions, the vessels will either sag or crack when placed in the furnace.

Mixing porcelain clays

Some clays are brittle, some are tough. This is the method of mixing used in all the factories.

Technically, the "bone" clay is kaolin, or China clay. It is an infusible substance derived from decomposed feldspar or granite. The "flesh" clay is a white, fusible material formed from a mixture of feldspar and quartz.

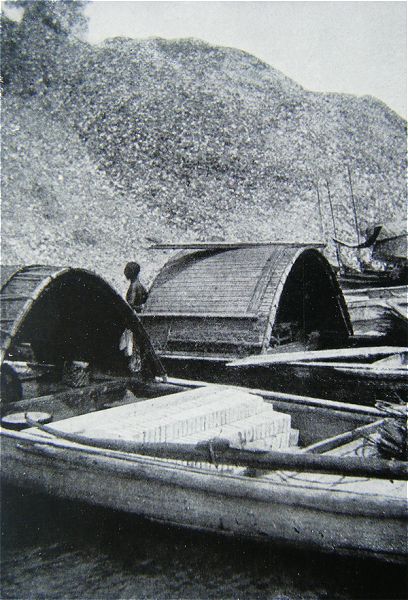

All of these clays are hauled to Jingdezhen in the form of soft, white bricks by small, flat-bottomed boats. Thousands of Chinese boatmen are engaged in this work.

Boats loaded with soft, white clay bricks for the porcelain factories

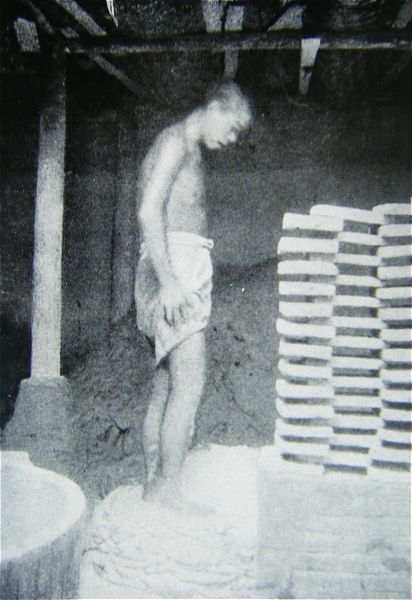

Kneading clay by foot-power after it has been thoroughly cleansed and sifted

After the clays are thoroughly cleansed, sifted and refined, they are kneaded together in varying proportions, usually by a bare-footed boy, until they are ready for the potter. The wet lump of clay is then placed on the knob of the potter's wheel.

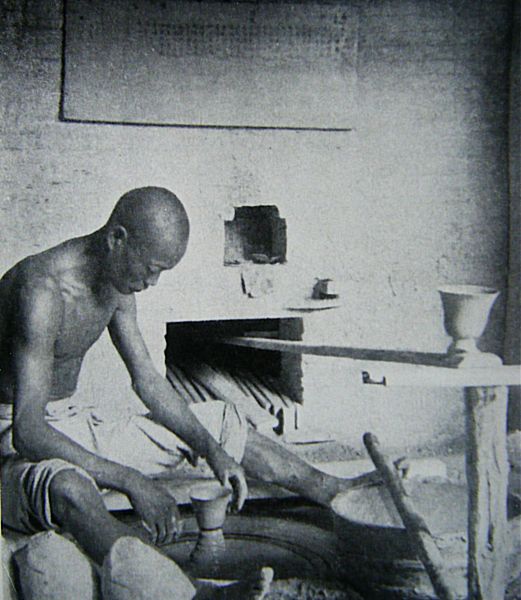

The potter at his wheel

After placing the ball of soft clay on the knob of the rapidly revolving wheel, he deftly forms a cup, vase or bowl with mechanical precision.

The potter's wheel, which was invented by the Chinese, is a huge circular machine, about four feet in diameter, made of heavy timbers to lend it momentum. It rests on a perpendicular axis in a slight depression or pit, into which water and debris rapidly drain.

The potter is perched above the wheel, with one foot on either side, in order to allow sufficient space for the movement of his hands. After revolving the wheel swiftly with a short pole, he deftly and with mechanical precision fashions a plate, bowl or vase. After years of practice, he can estimate to within a hair's breadth the proper size.

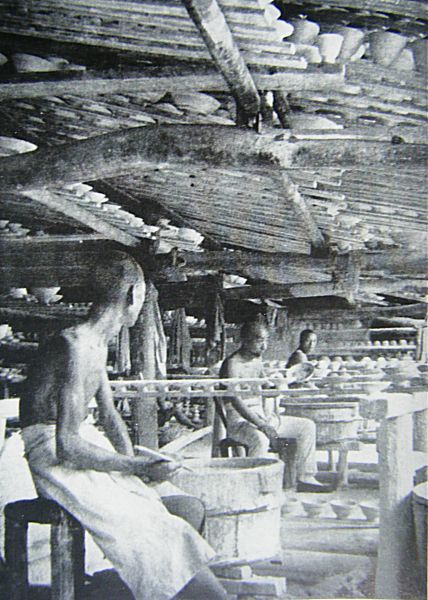

Artists engaged in decorating porcelain in one of Ching-teh-chen [Jingdezhen] largest factories

Note the thousands of pieces stored overhead, all awaiting the under-glaze decoration. After being decorated, the glaze is applied in one of several ways - by dipping, by being blown on through a tube, or by sprinkling. The piece is then ready for the furnace.

The piece is then removed and placed on a long tray in front of the potter, where it awaits the next artisan. Handles and other decorations, made in molds, are added, and then the whole is scraped smooth and allowed to dry until it is ready for the next process – the under-glaze decoration.

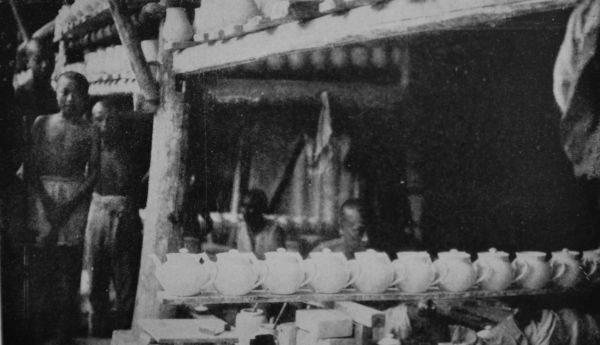

Where the teapot multiplies

In the center of the porcelain industry the product is classified according to shape, as follows: "Yuan c'hi", "tso c'hi" and "tiao hsiang" - round ware (cups, bowls, saucers, and plates), irregular rounds (teapots, vases, etc.), and irregulars (statues, trees, etc.). The factories are likewise classified according to the shape of the ware they manufacture.

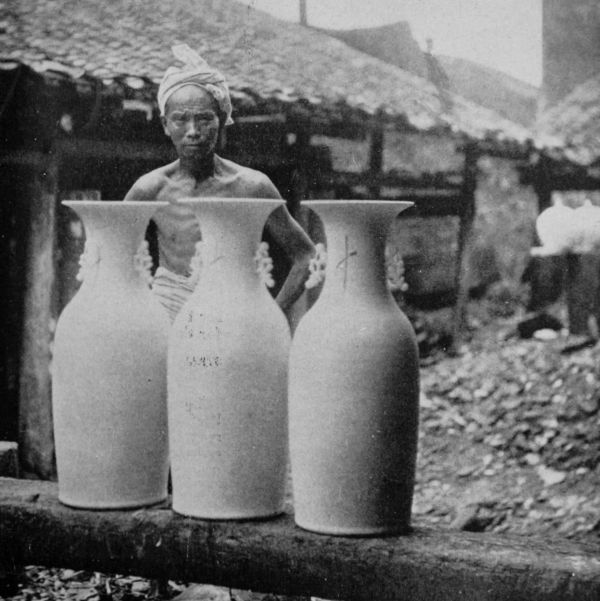

A potter and his unfinished ware

Almost large enough to have served as the jars in which Ali Baba's Forty Thieves concealed themselves! Those jars of Arabian Names might have been made in Jingdezhen, for China's ancient porcelain center was manufacturing such wares as early as 220 A.D.[No, not really, production here started in Five Dynasties and Ali Babas jars would more likely have been Pegu or Martaban jars, and not from Jingdezhen at all. / JE]

The way in which porcelain is moved from place to place.

This milk-like liquid is the porcelain glaze ready to be blown or brushed upon the potters' product

Several basic colors, like blue and red, can be painted on under the glaze. The glaze is next applied in various ways – by dipping, by blowing on with a tube, or by sprinkling. After the mark has been added the piece is ready for the furnace.

One method of applying glaze

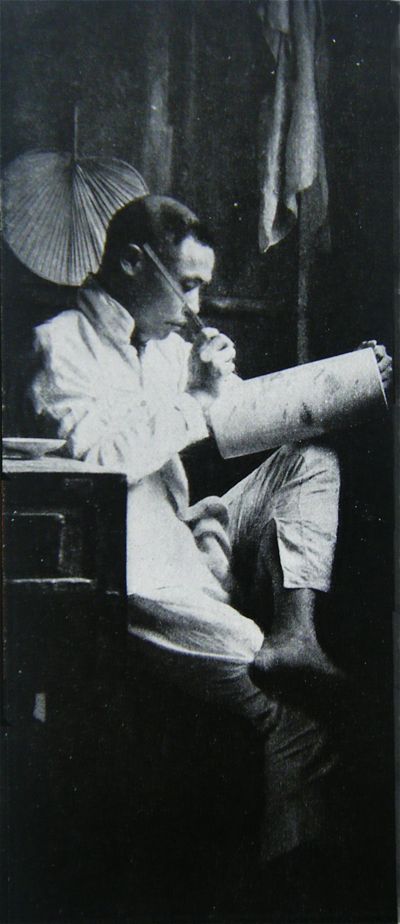

Here the operator is blowing the glaze through a bamboo tube as the vase is slowly revolved by his toe.

Porcelain placed in the kiln to be fired has to be protected in strong, cylindrical clay vessels, called saggers. These trays can be used from three to six times before they are ready for the scrap heap on the river bank. Every piece of porcelain, as it is set into the sagger, is placed on a small, round, clay chip, sprinkled with straw ashes. This prevents fusing together of the two pieces.

The fuel for the furnaces at Jingdezhen is of two kinds – straw and wood. Coal has been tried, but it was found that its fumes discolored the porcelain, and accordingly its use was discontinued. Straw is used to burn only the coarser ware.

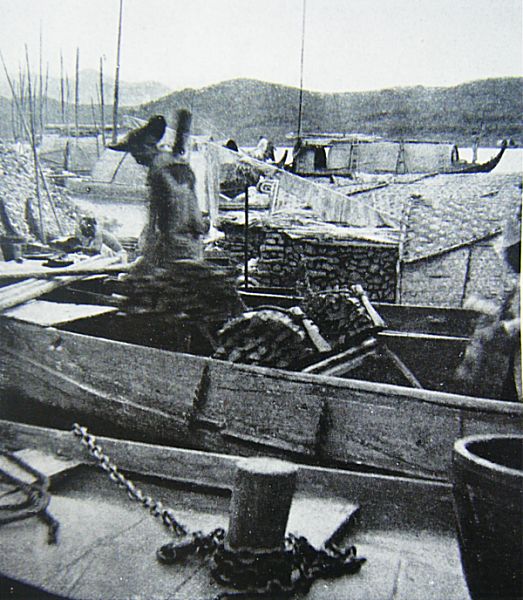

Thousands of boats are engaged in hauling wood for the porcelain furnaces

The fuel problem is a very acute one and it is only with greatest difficulty that wood can be secured at all. The neighboring hills have long ago been deforested, and firewood must be transported to Jingdezhen in river boats, often from sources 200 or 300 miles distant. Boats piled high with straw, projecting over the sides almost to the capsizing point, are common sights all along the river. Wood-boats, too, are seen everywhere.

The kilns are large, egg-shaped ovens of brownish brick, fifty feet long and twelve feet high at the highest point. Because of the intense heat, both the kilns and chimneys must be rebuilt annually.

Every piece of porcelain is placed in the furnace with great precision and arranged according to the temperature which is necessary for its complete firing. Only certain pieces can be placed at the top of the kiln.

The furnace when full is entirely bricked up, and the whole contents are kept at a temperature of 1,600 to 2,000 degrees centigrade, usually for a night and a day, after which the kiln is allowed to cool off, and in due time the porcelain is removed. It has been found that one kiln is large enough to keep nine or ten factories in operation.

This completes the process if no decorations other than the under-glaze paintings are desired, but if more elaborate colorings are used, further burnings in a smaller kiln take place. In applying other ornamental designs the artist often spends weeks, or even months, in completing a single piece, as was the case with a beautiful vase portraying the five relationships, which we had the pleasure of inspecting in the leading factory in the city.

We found porcelain to be classified, according to shape, as follows: "yuan c’hi" or round ware, which includes cups, bowls, saucers and plates; "tso c’hi" or irregular rounds, including teapots, vases, and small, flat ink and paint boxes; "tiao hsiang", or irregulars, such as images, statues, representations of trees and other objects.

An interesting feature of the manufacturing process is that the factories are also classified according to the shape of the piece they produce – that is, Mr. Wang makes only round ware, or he may even confine himself to the manufacture of bowls, while Mr. Li’s factory is devoted entirely to the production of teapots.

Clustered around the Fukien Guild Hall, in the eastern part of the city, for example, we found about twenty Fukienese families devoting their entire time to the making of images and statues, such as the God of War, Goddess of Mercy, the Three Stars – Happiness, Longevity and Posterity – and the Gods of Harmony. Among the collection we also noticed some obscene pieces.

There is only one plant in Jingdezhen which produces all varieties of porcelain and pottery – the Jiangxi Porcelain Company. It was organized several years ago by a number of prominent stockholders on a modern basis. No foreigners are connected with it in any capacity. We hear a good deal these days about the inability of Chinese to run their own business firms, but the success of this company, which received the grand prize for the best exhibition of porcelain at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1915, seems to indicate that they have some business capacity.

Cheap porcelain piled high along porcelain street.

Among the four hundred male employees of this concern are one hundred formerly engaged by the Imperial Pottery. In fact, with the downfall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the Jiangxi Porcelain Company took over practically the entire plant of the famous old factory.

The Imperial Pottery had a long and noble history. It was established in the Sung Dynasty, which lasted from 960 to 1279 AD. The emperor Chiu Tsung, who founded the dynasty, established the manufactory at Jingdezhen, and down through the centuries each succeeding emperor gave it his support and encouragement. It is reported that it was a part of the Yuan Shikai’s imperial plans to reopen the pottery on his ascendancy to the throne. This is but one of the would-be Emperor’s dreams that was cut short by his sudden death.

Although the empire no longer exists, porcelain is still used in large quantities by officials in Peking. It was my pleasure on several occasions to meet at feasts President Hsu His Chang's representative [Xu Shichang, President of China (1918–1922)], who had been in Jingdezhen for several months purchasing special wares to be used as gifts in the capital. We visited the factory which filled his orders and saw there dozens of vases, in every stage of development, later to be presented to foreign ambassadors and Mongol princes.

There is no unemployment in Jingdezhen. Work is plentiful, but industrial conditions are bad. Long hours, poor food, no rest days and unsanitary living conditions cause a great deal of dissatisfaction among the laborers.

Workers are organized, first according to the parts of the country from which they come – Jingdezhen, from Anhui and all other provinces. They are further formed into guilds, according to the kind of work upon which they are engaged. Strikes are infrequent, but there is seldom resort to violence. The Chamber of Commerce is a regular mediator.

Many women are engaged in various forms of porcelain production, such as painting, engraving, and lettering. The apprentice system prevails throughout the industry, as in every trade in China. It was interesting to note the artistic ability of a number of small boys engaged in paint birds, flowers, fish and bats, the last being an omen of good fortune.

Wages range from ten cents to one dollar per day, Mexican, for potters and molders. This includes food and room. The artist's wage ranges from twelve cents to three dollars per day, varying not according to the number of hours but, but according to he number and quality of the pieces produced. But no artisan must work too long. If a man is found doing too much and working beyond the time limit, he is set upon by his fellow workers and severely beaten.

We learned from the revenue collector that about $5,000,000 worth of porcelain and pottery is shipped out of Jingdezhen every year. Every piece has to be hauled down the river in small boats to Raochow [Jaochow, today 'Shangrao'], whence it is forwarded in large junks to Shanghai and other cities. Most of this is for domestic use, the Chinese not yet having learned the value of stimulating international trade.

The best decorative artists receive three dollars a day (Mexican)

The unskilled wielders of the brush can earn as little as fifteen cents a day, however, the men are paid not by the hour but according to the quality of their work and the number of pieces finished.

Making the famous rice-pattern ware

Patient skill and no small amount of time are required in making this pattern, which is known in Jingdezhen as "Ling lung" [devils' work]. It is made not by pressing kernels of the grain into the wet clay, but by cutting the apertures with a sharp knife, after which the holes are filled by repeatedly dipping into the glazing fluid.

Perhaps the most popular design of porcelain with foreigners is the "ling lung" or rice pattern found in dishes, cups and bowls. The Chinese have learned the art of producing foreign-style dinner sets in this pattern and are finding a ready market for them.

Patient skill and no small amount of time are required for the making of rice pattern. The wet clay is first formed into a crude cup or plate on the potter's wheel. After the piece has dried for several hours or for a day, it is carefully scraped with a special kind of knife which conforms to the curvature of the vessel. The next step is to cut in the kernel-shaped holes. This is done by a skilled workman, who uses a small, flexible steel lancet.

I had always thought that the rice pattern was made by pressing kernels of rice into the damp clay. It was not until I saw the actual process that this erroneous impression was corrected. After these small apertures have been completed the vessel is ready for the under-glaze painting. Decorating finished, the next step is to apply the glazing fluid. This is a thin, milky substance of high-grade porcelain. Sometimes the bowl is dipped, but the cold, raw liquid is usually put on with a soft wool brush.

The operation is repeated about thirty times, with an interval for drying, until all the holes are filled. Five or six coatings only can be applied in one day. The piece is then fired in the usual manner, and comes out of the furnace with the filled holes standing out in beautiful translucent designs.

The firm exporting the largest quantity of porcelain from Jingdezhen is a Chinese company in New York City.

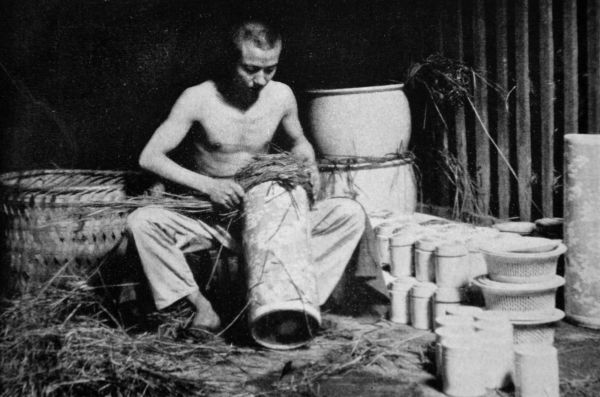

Packing porcelain in rice straw to be shipped to America

The firm exporting the largest quantity of porcelain and pottery from Jingdezhen is a New York concern. Each piece is carefully packed by hand in rice straw before being packed in large boxes.

Each piece is carefully packed by hand in rice straw before it is packed in large boxes. These foreign boxes are made in Jingdezhen and after being marked both in Chinese and English, are shipped directly to New York.

The outstanding impression which a Westerner carries away from this teeming industrial city is the primitiveness of the methods in use. In not a single shop or factory does on find modern machines. Not even the simplest mechanical devices for operating a series of wheels by means of belts are to be found. Every pieces of porcelain is turned out by hand- or by foot.

Yet it is astonishing how much these patient workmen produce with their obsolete methods and crude devices. New ideas penetrate interior China slowly, but with the opening of the Nanking-Nanchang Railway, which has been planned and surveyed, Jingdezhen will assume as position of commercial influence that will astonish the world. The enormous clay deposits, together with the quantity of cheap labor, touched by the magic hand of a twentieth century artist engineer, will push this old and interesting city into a position that will far outshine her ancient glory.

This article is from the November 1920 issue of The National Geographic Magazine, page 391-406. The article was written by Frank B. Lenz and illustrated with photographs by the author. The text here is a more or less verbatim transcription of the original text. Spelling of names originally in Wade-Giles has been changed into Pidgin where this seemed fit, with the original spelling given once within brackets. Where I have found any errors and omissions in this text, you will find my comments there also in brackets. This page as it appear on this web page is copyright © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Gotheborg.com, Sweden 2010