This page is only one of many thousands of Gotheborg.com Help and Information Pages, offering specialized knowledge on Chinese and Japanese Porcelain, including a Glossary, Q&A, Chinese and Japanese Porcelain Marks, Chinese Porcelain Exhibition and Excavation reports etc. For personal help and far more information, join our Discussion Board or use 'Ask a Question' for quick email consultations. For full text and better navigation, use a full-screen device rather than a mobile phone, that offers only limited content.

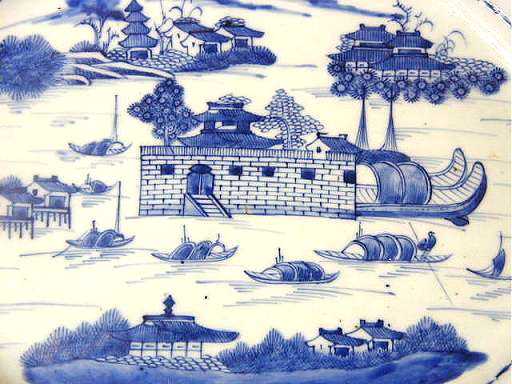

Chinese Blue and White Export Porcelain, depicting the "Dutch Folly" fortress on the Pearl River in China, about 16 x 13 inches. In the center, the fortress, boats of various sizes, islands, pagodas, flowering trees, unglazed flat bottom. Decoration based on C. G. Ekebergs engraving of 1773. Made for the American market c:a 1790-1800.

The background of this piece is the bustling activities in Canton, Chinas main trading port to the West during the 18th and 19th century.

The rise in trade between China and the West throughout the 18th-century provided the impetus for the establishment of many workshops in Canton making wares for the Western market.

These trade wares included porcelain and different pottery objects, lacquer objects, fans and, of course, China trade paintings.

The majority of all porcelain bought in Canton was ordered by the home office of the various East India Companies, and of mediocre quality.

Another thing altogether was the private trade and the souvenirs that was brought back by sailors and the tea, silk and porcelain trading merchants. They had only a limited space onboard in their private chests, and were anxious to fills their cramped living space onboard only with things of the highest value and those that would bring the highest price possibly when back home in Europe or America.

One of the most popular souvenirs - besides silk - to the beloved ones back home, was China trade paintings painted in a variety of mediums. Oil paintings are well known; some were painted on conventional paper of a type still available in China today. Others were painted on mirrors. The most delicate and detailed were painted on thin, brittle and almost translucent paper made from the fibrous pith of the Chinese tongcao plant. Pith paper, commonly mistaken as rice paper.

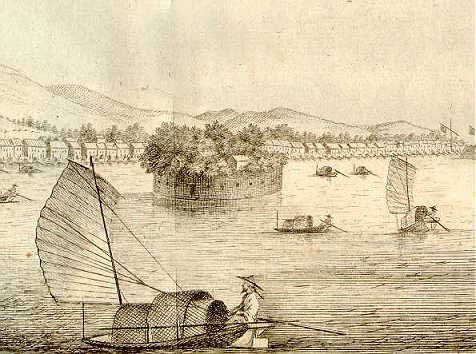

The Whampoa ancorage at Pearl River in an 18th century trade painting based on Ekebergs prints of 1773.

When in China western merchants alighted from their ocean-going vessels at Whampoa on Pearl River close to Canton, onto small river launches which took them upstream to the foreign factories, a journey of about ten miles.

During this trip they passed two “folly” forts, so called possibly because they were of questionable defense value. The one nearer to Whampoa, more oblong than round, was known as the “French Folly”. The second, larger and more famous fort, a truly round structure within the precinct of the city just to the west of the foreign factories, was known as the "Dutch Folly".

The "Dutch Folly" in Pearl River close to Canton, detail of engraving in C.G.Ekebergs diary, 1773.

In 1773 Captain Carl Gustav Ekeberg published his recollections of several trips to Canton in the service of the Swedish East India Company. This book was illustrated with several engravings based on his own drawings. This book was carried back to China, and these illustrations very likely founded a whole new genre of Chinese export products; namely, the various scenes foreign merchants and sailors saw when arriving at Canton.

Most paintings with these motifs are today in museums or incredibly expensive.

The most popular of these views is the view of the foreign factories, which were the merchants' offices at the Canton waterfront. Seen at far right of Ekebergs original print is the "Dutch Folly" (see below for a detail). It is repeatedly depicted in many pictures from the mid-18th century forward with a small building within its walls surrounded by quite dense vegetation.

When the first American East India ship, "The Empress of China"”, reached Canton for the first time in 1784, this platter could have been one of the first things that caught the American tea and porcelain merchants' eyes.

Jan-Erik Nilsson