This page is only one of many thousands of Gotheborg.com Help and Information Pages, offering specialized knowledge on Chinese and Japanese Porcelain, including a Glossary, Q&A, Chinese and Japanese Porcelain Marks, Chinese Porcelain Exhibition and Excavation reports etc. For personal help and far more information, join our Discussion Board or use 'Ask a Question' for quick email consultations. For full text and better navigation, use a full-screen device rather than a mobile phone, that offers only limited content.

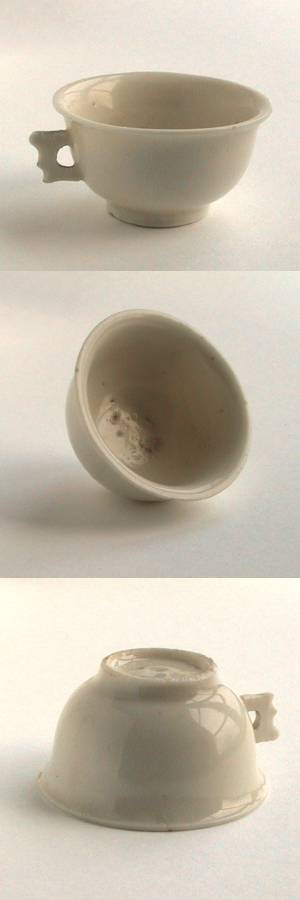

Sacrificial cup, Fujian Blanc-de-Chine, 18th century, Qing dynasty.

"Popularity" of a certain field of collecting often comes with publicity. What brought modern public attention to white wares as a group, was as I see it J.P. Donelly's book "Blanc-de-Chine", through which he helped collectors to identify their pieces.

A second important factor was the fame of the Carl Kempe Collection, formerly at the Swedish Ekolsund Castle.

What is most discouraging for collectors is problems with dating and attribution. Blanc-de-Chine is a classical ware. In the old books it is described as a "white ware from Dehua in Fujian province".

Recent books does not focus very much on Blanc-de-chine and as it seems to me, a lot - not to say the most - of what we call "Kangxi period Blanc-de-chine from Fujian" is actually Qianlong or later period pieces from the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province. Take a look at the small sacrificial bowl to the right. This is how an early 18th century, Dehua, Blanc-de-chine piece should look like. As a further significant feature we also have a molded foot rim. Compare this piece with the dead white Jingdezhen pieces, and you will see what I mean.

So, for the moment I would say it is as good a time as ever to start collecting Blanc-de-Chine since the average awareness of this ware is low.

Just avoid paying "Kangxi period Blanc-de-chine" prices for modern slip cast white ware pieces.

Jan-Erik Nilsson

This page is only one of many thousands of Gotheborg.com Help and Information Pages, offering specialized knowledge on Chinese and Japanese Porcelain, including a Glossary, Q&A, Chinese and Japanese Porcelain Marks, Chinese Porcelain Exhibition and Excavation reports etc. For personal help and far more information, join our Discussion Board or use 'Ask a Question' for quick email consultations. For full text and better navigation, use a full-screen device rather than a mobile phone, that offers only limited content.

I read with great interest your Q&A writeup on Blanc-de-chine. Your writeup seems to indicate that Blanc-de-chine from Fujian has a slightly creamier look than pure white.

I own three Blanc-de-chine pieces that range in period from the 17th to the early 20th century. Two pieces have a similar type of creamy white glaze. But the third piece which is a vase, is almost pure white. The seller of the piece told me, and also wrote in the bill of sale that the piece is a dehua Blanc-de-chine vase dating back to the 1740s.

My question is: Did the kilns of Dehua ever produce white looking Blanc-de-chine porcelain besides the "creamier tone" similar to the two other pieces I own? Is it possible that multiple tones of white were produced at Dehua? Or is it likely that the vase more likely originated in Jingdezhen? Thank you.

I have given the subject a lot of thought and I have not examined that many certain "Dehua" wares to be really sure about what was actually made there.

I am quite certain - thought - about what was and still are possibly to make in Jingdezhen.

They have had and still have a tremendous output of all kinds of wares including of course, white undecorated pieces.

So, I am therefore inclined to believe that most of the pieces that looks like Jingdezhen ware - i.e. actually most white pieces - really are Jingdezhen ware and not Dehua (Fujian).

In looking for Dehua wares I think we must look for something that distinguish them from Jingdezhen other than the fact that they are undecorated, white and of porcelain. The Ivory tone is one of them. An interesting fact is that this Dehua ivory tone is sometimes only visibly inside the paste of the pieces and then only seen when held up against a light.

We also know that the Dehua porcelain paste seems to be somewhat different from the Jingdezhen so as to make it difficult to decorate with underglaze blue. This might of course have been depending of the cobalt and not the paste - but somehow it seems as a logical explanation for specializing on undecorated pieces.

So, to sum this up I feel like your thought that the vase more likely originated in Jingdezhen is correct. But, there is also a question of style and I have not seen the piece. Somehow I feel that the Jingdezhen pieces were more run of the mill - mass produced pieces - but that is just my feeling for this.

Thank you for bringing the subject up. Your further thoughts on this are most welcome.

Jan-Erik Nilsson

This page is only one of many thousands of Gotheborg.com Help and Information Pages, offering specialized knowledge on Chinese and Japanese Porcelain, including a Glossary, Q&A, Chinese and Japanese Porcelain Marks, Chinese Porcelain Exhibition and Excavation reports etc. For personal help and far more information, join our Discussion Board or use 'Ask a Question' for quick email consultations. For full text and better navigation, use a full-screen device rather than a mobile phone, that offers only limited content.

For further thoughts on this I publish the following insightful comment from a friend at the Hong Kong University.

Dear Mr Nilsson,

The ivory tone you mentioned inside the piece, when held up against the light, might be the sign of early Dehua wares - Ming or earlier. It is a light "pink" colour of the paste, under the clear glaze.

From early Qing onwards the pink paste disappears and becomes a silvery white, snow white and more glossy on the whole.

To explain the reason for the ivory, pink paste for Ming or earlier Dehua, some years ago I read in a book on Dehua ceramics while traveling in the area, that Marco Polo had recorded what he saw of the preparation of Dehua wares while he was passing through the area on his way back to Europe.

He saw that heaps of soil were dug up and left on the field. When enquiring, he was told the soil were left for "seasoning" i.e. to be exposed under sun and rain for a hundred years or two - to be used by the next generations. Marco Polo also took notes of the cost for the wares and bought some pieces. The story has it that at least one piece is now in the hands of a museum in Vienna.

Jingdezhen does not seems to have had this tradition of seasoning the clay, which might explain a difference compared to the Dehua clay.

While typing this I also got to remember the pirates from Japan that terrorized this area from late Ming to the early Qing period. The troubles were grave, kilns were out of action as the potters were fleeing away. During the mid Qing period, troubles were going out of hand and the Imperial government ordered the inhabitants to leave the coastal area from Fujian to Kwangtung (Guangzhou) and to move inland. I tend to believe that the moving of the inhabitants have caused the downfall of the Dehua kilns so much that even the folks of Dehua around 1920 to 1970 did not realize how great their home kilns once were. It could be that when the potters returned, the seasoned clay were finally used up and unseasoned clay had to be used.

The change of clay could also be explained by the high European demand for white wares from Dehua and Europe that might have caused the seasoned clays to be used up.

Since Jingdezhen and Dehua are quite close together the same runners also moved around these two areas frequently, so both kilns must have be influencing each other in style and skill.

As for telling the porcelain from these two kilns apart I would go for the style, apart from the paste and glaze since Dehua are more conservative in the forms. The blue and white of Jingdezhen and Dehua are also difficult to tell apart.

I think the first proper study of the Dehua kilns was only made in the 1980s, the first formal exhibition was held in Hong Kong University Fung Ping Shan Museum around 1990. A very good book was published for this exhibition. There is also a new book : Dehua Folk Blue-and-White Wares, by Chen Jianzhong, Dehua Ceramic Museum, Fujian. ISBN 7-5010-1166-4. Its a rare book on this subject but a good one, first published on 8/99.

Simon Ng

City University of Hong Kong

Dear Sir, Thank you for your thoughts to which I only want to add a few comments.

It is interesting to note that you feel certain there is a visibly change in the porcelain body of the Dehua wares during late Ming/Early Qing. This is - in that case - the same as what is happening in Jingdezhen wares at this time.

Regarding the Jingdezhen wares, I have felt this was due to the change of source of the Kaolin part of the porcelain clay, when they abandoned the Gaoling (Kaolin) ridge source by the end of Ming. All my personal observations seems to fit with that, but whether this is the full truth I don't know. This change of clay source for the Jingdezhen wares any way seems to coincide perfectly with the reduction of the iron content in the Jingdezhen paste and therefore also its tendency to turn a rusty red where exposed during firing.

From the Marco Polo account one might be prepared to draw the conclusion that the Dehua potters were working with one - natural - clay and not mixing it with any Kaolin clay which was the Jdz practice at about the time of the Yuan dynasty (12th century).

Regarding the "seasoning" of clay I would in this rather recognize a well known pottery technique to make a clay more plastic, but for this end, just a few years should do fine. What happens is that that porcelain clay often consist of small mica particles in the shape of very small "flakes. A few years of "seasoning" makes these particles organize themselves as the cards in a deck of cards, which makes the clay more slippery - more "plastic" - and more suitable for all kinds of potting.

I don't know what this might add up to, but since the book title you are mentioning specifically deals with Dehua blue-and-white I feel we might first have to define if they by "Dehua" are referring to Fuyao, Jianyao or specifically only to the Dehua district white wares.

Another thing that would be most interesting to investigate would be the influence from the Northern Ding wares, which must have arrived to the south of China along with the Song court in 1127. Could it be more than a coincidence that the pink/ivory tone we can see in the (early) Dehua wares is also a prominent feature of the Ding yao?

Thank you for your help and interest.

Best regards,

Jan-Erik Nilsson