Marks of earlier periods have been used throughout almost the history of Chinese porcelain. Almost at the same time that the Chinese invented porcelain they also invented marks - and copies - sometimes to keep track of who made the piece, who ordered it, where it was made, for what purpose, sometimes to honor the original, sometimes to deceive, sometimes to replace, sometimes just to meet a demand or something just for fun. There is one known mark that is obviously a caricature of someone...

Marks on porcelain are useful timestamps, depending on how they are written, regardless of what they actually say. So, you don't need to be able to actually read what they say to benefit from their presence. Despite the bad reputation Chinese porcelain marks have earned themselves for their inherent lack of authenticity, porcelain marks remain one of the best means we have to identify the period during which a certain piece was made. Correctly understood, they are like a timestamp and sometimes like a fingerprint of the potter and his time. You just need to know how to interpret what you see.

This marks section currently illustrates more than 1,560 porcelain marks, including both Chinese and Japanese. In the navigation panel, you will find the main groups. Within each page, further links lead to even more marks, where many similar marks are grouped together. Whenever possible, all marks have a link to an enlargement for detailed study.

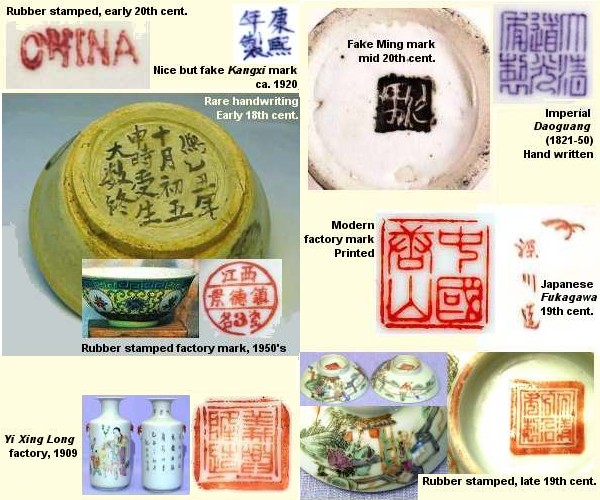

The marks may be bewilderingly difficult to recognize, and it might even be hard to discern whether they are Japanese or Chinese. As a general rule, Chinese marks are more regular, with mostly six or four characters placed inside a round or square frame. Japanese marks are typically irregular, with two or any odd number of characters, different colors, and are more artistic in style, or printed. Try to see if you can spot the one Japanese mark in the picture at the top of this page.

To somewhat organize this subject, marks could be red or blue, handwritten, or applied with a rubber stamp. The four red marks in the picture above are Chinese and rubber-stamped, which usually indicates "around 1900". One modern Chinese mark is printed, and one Japanese mark is a hand-drawn 19th-century Fukagawa 'orchid' mark.

It's a very simplified rule, but statistically speaking, marks from the mid-19th century or later are mostly red, while older marks are predominantly blue.

Four-character marks with raised enamels suggest that the piece was made at the Imperial workshop in Beijing, which is very rare but could be authentic. However, precisely because of this rarity, it is also often imitated on modern souvenir porcelain vases.

Marks incorporating Western characters do not appear before the 1890s, and almost all we encounter are from after the 1950s.

Most porcelain marked 'Made in China' usually dates from the 1970s or later.

Theoretically, any mark on the base of a piece of Chinese porcelain should indicate the reign title of the Emperor during whose reign the piece was made, assuming it was commissioned by that specific court.

In an ideal world, pieces bearing the mark 'Da Qing Qianlong Nian Zhi' would have been commissioned by the Chinese court for use during the Qianlong period (1736-1795) of the Qing dynasty. It would be reassuring if this were always the case; however, these marks are usually found on very recent souvenirs intended for sale to tourists. Consider this: while genuine antiques do exist, authentic Imperial Chinese Porcelain pieces with a genuine Imperial mark are exceedingly rare. And with every hand a piece have passed through, someone will have had their hope raised for a while.

On the other hand, as I write this, I've received an email about a narcissus bowl purchased at a flea market in California for 50 cents. It turns out to be a non-imperial, yet still significant, Guangxu Mark and Period piece dated to 1887, and worth considerably more than 50 cents. So much for that piece of advice... Let's examine the Imperial reign marks as well, then.

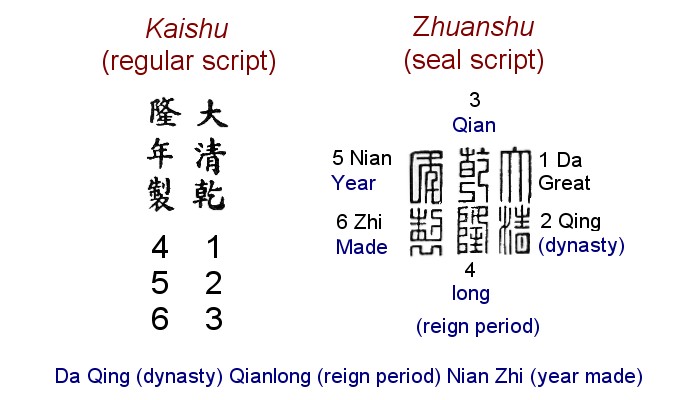

Below is illustrated two six character marks from the Shun Zhi period (1644-61). The left mark is written in Kaishu or "regular script" script, that is the most common in Chinese writing. The right more angular mark is in zhuanshu, or "seal script". The latter mark is technically speaking a line drawing, and does not reflect any style of handwriting. Zhuanshu, means literally 'decorative engraving script', which reflects its role for writing seals and ceremonial inscriptions.

In 1736 Hongli was selected to become the Qianlong Emperor on the basis of merit. Qianlong 乾隆 (Meaning 'Lasting Eminence') became the name of his reign (1736-95). Qianlong was the sixth Manchu emperor and the fourth emperor of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Imperial reign marks are like all old Chinese texts read from top to bottom and from right to left. The first character is the top right character 1 that reads Da meaning "great". This is normally the first character in most Ming (1368-1644) or Qing dynasty (1644-1911) marks. This character is easy to memorize, and then you will always know which way is "up". Look at it like an upside down capital "V" with a stroke across, or a person standing with legs wide apart and arms outstretched, or in seal script like a four pronged pitchfork. In both cases, it means "Great".

Character 2 tells us the dynasty as Ming or Qing. Earlier than that, porcelain did not have reign marks.

Next two characters 3 - 4 are the emperors nianhao or reign title, name of the era, motto, or slogan. It is not the emperors actual name which in the case of Qianlong (乾隆) was Hongli.

The last column with the last two characters 5 - 6 merely say Nian Zhi which actually means "Year Make".

Imperial Chinese reign marks are almost always written in two or three vertical columns or very rarely in one horizontal row (Ming) or two (Qing). Worth mentioning is that around 1950 the Chinese modernized their written language and started to write from left to right, as in the west. This practice also found its way to most modern porcelain marks from that time and later.

Chinese reign marks are read in columns, right to left and top to bottom. Mark on the left is written in traditional kaishu script while the mark on the right is written in stylized zhuanshu seal script. The first two characters in the rightmost column identify the dynasty – in this case ‘Da Qing’ 大清 or Great Qing dynasty. The next two characters in the middle column are the name of the emperor – in this case Qianlong 乾隆. Last two characters ‘Nian Zhi’ 年製 simply mean made (during the reign of). Thus, we can read this reign mark as Made in the Great Qing Dynasty during the reign of the Emperor Qianlong.

During the Kangxi (1662-1722) period, marks with symbols and characters other then the reign title became common. The characters are often the name of the place the piece seems to have been made for. These are called "Hall marks". It is also interesting to remember that specifically 18th century export porcelain to the west is almost never marked while most pieces made for the Chinese common people are actually quite often marked. All this commoner's porcelain is called Min yao meaning "people's wares" as opposed to the Imperial wares which is called Guan yao.

Unfortunately this is something that is very hard to learn and is only possible by extensive studies and comparison of genuine examples. This goes for the shape, the porcelain body itself, the glaze, the cobalt, foot rim, decoration and down to the individual brush strokes in marks and decoration and all this is combination.

From this perspective it is actually very helpful to begin by studying the marks on the bases of the purported Imperial porcelains since this is limited in scope. It was not that many different calligraphers entrusted with the job of adding the Imperial seals to the bases of the porcelain that we eventually can't learn to recognize the handwriting of these experts, and eventually the small but telltale differences in how they drew their brush strokes.

For a first impression it is usually enough to look at the general design of the mark, if the strokes are absolutely symmetrical and if the mark as such is perfectly square and even, if the characters are of equal size, if the strokes are evenly and precisely drawn etc.

To learn how to see this yourself it would be enough with a few years careful studies. The easiest is to compare with genuine published examples as you would with a stamp or a bill, that "looks" all right but you don't know for sure, so you put them side by side and - compare.

That is how the experts do it, and there are no shortcuts available.

I can't emphasize enough how much you would benefit from a membership of the Gotheborg Discussion Board if you want to know more about this. On the Board there are many seasoned collectors and experts who can tell you what you have, and explain the difference between seemingly very similar marks.

Jan-Erik Nilsson

Gotheborg.com

The marks section of Gotheborg.com was initially established in May 2000 thanks to a generous donation of approximately one hundred images of Japanese porcelain marks, by Karl-Hans Schneider from Euskirchen, Germany. This contribution provided a modest yet substantial beginning of the Marks Section. It was a kind gesture that I really appreciated.

Of the many later contributors, I would especially want to mention Albert Becker, Somerset, UK, who was the first to help with some translations and comments on the Japanese marks. His work was then greatly extended by Ms. Gloria S. Garaventa, after which Mr. John Avery looked into and corrected some of the dates. Most of the Satsuma marks were originally submitted by Ms. Michaela Russell, Brisbane, Australia. A section which was then greatly extended by Ian & Mary Heriot, a large amount of information from which still awaits publication.

A warm thank you also goes to John R. Skeens, Florida, U.S.A., and Toru Yoshikawa for the Kitagawa Togei section, and to Susan Eades for her help and encouragement towards the creation of the Moriyama section. For the last full overhaul of the Satsuma and Kutani sections, thank you to Howard Reed, Australia. The most recent larger contribution was made by Lisa M. Surowiec, New Jersey, USA.

In 2004 and from then on, my warm thank you goes to John Wocher and Howard Reed, whose knowledge and interest have sparked new life into this section and given reason for a new overhaul. Thank you again and thank you to all I have not mentioned here, for all help and interest in and contributions to our knowledge of 20th-century Japanese porcelain.

The Chinese marks section would not have been possible without the dedicated help of Mr. Simon Ng, City University of Hong Kong, whose translations and personal efforts in researching the origin and dates of the different marks have been an invaluable resource. It has since been greatly extended by several contributors such as Cordelia Bay, USA, Walt Brygier, USA, Bonnie Hoffmann, Harmen Lensink, 'Tony' Yalin Zhang, Beijing, 'ScottLoar', Shanghai, Mike Harty, and many more expert members of the Gotheborg Discussion Board.

A number of reference pieces have also been donated by Simon Ng, N K Koh, Singapore, Hans Mueller, USA, Hans Slager, Belgium, William Turnbull, Canada, and Tony Jalin Zhang, Beijing.

All images and text submitted by visitors and published anywhere on this site are and remain the copyrighted property of the submitter and appears here by permission of the owners which can be revoked at any time. All information on this site, that are not specifically referenced to peer reviewed sources, are the personal opinions given in good faith by me, my friends and fellow experts, based on photos and the owners' submitted descriptions. They are not to be used for any financial or commercial decisions, but for educational and personal interest only, and can and will be changed as further information merits.

For further studies, Encyclopedia Britannica is to be recommended in preference to Wikipedia, which, not being peer-reviewed, might contain misleading information.

Web design and content as it appears here © Jan-Erik Nilsson 1996-.