This page is only one of many thousands of Gotheborg.com Help and Information Pages, offering specialized knowledge on Chinese and Japanese Porcelain, including a Glossary, Q&A, Chinese and Japanese Porcelain Marks, Chinese Porcelain Exhibition and Excavation reports etc. For personal help and far more information, join our Discussion Board or use 'Ask a Question' for quick email consultations. For full text and better navigation, use a full-screen device rather than a mobile phone, that offers only limited content.

I am currently living in Shanghai, China. When visiting antique stores in the city and some of the neighboring old villages invariably the dealer/owner will tell me it is "Ming, very old".

Are there any significant markings, etc. to look for on these pieces? Can you suggest any books to read on pieces from this dynasty?

There is no easy way to separate antique Chinese porcelain pieces from fakes or even just modern pieces. The best way to learn is to visit dealers and museums, ask questions and read everything available on the subject and most important get to handle the pieces.

You could also bring a friend that is in the same process of learning. In that way you can use four eyes - who does see more than two - discuss your experiences and compare notes so to speak.

There is also a lot of books around on the subject. I especially suggest that you browse the museum shops for what is locally available.

One of several old books on the subject I like is Oriental Blue & White by Sir Harry Garner, published 1954. The third edition is the best. He is very readbly even if later research has proved him wrong in some details, but that will eventually happen to everybody, and does not detract from the overall understanding his books brings.

The most charming book that is likely ever be published on the subject is A. D. Brankstone Early Ming Wares of Chingtechen. This book is a collectors item in itself and I highly recommend it for the understanding of early Ming.

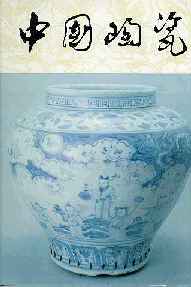

To help you out a bit with a book that is NOT out of print, yet, I enclose a scan (right) of a very important book on provincial Ming (minyao - peoples ware) that should be available at least in China. You might be able to get it at the museum shop at the Shanghai Museum. Even if you don't read Chinese the pictures are good and you should be able to recognize the period characters in the captions.

To help you out a bit with a book that is NOT out of print, yet, I enclose a scan (right) of a very important book on provincial Ming (minyao - peoples ware) that should be available at least in China. You might be able to get it at the museum shop at the Shanghai Museum. Even if you don't read Chinese the pictures are good and you should be able to recognize the period characters in the captions.

At the Shanghai Museum Shop there should also be a book by Bi Keguan, Chinese Folk Painting on Porcelain, available. I have bought a copy there myself not long ago. He has an important point in speaking for the "peoples porcelain" as an art form separated from the imperial wares. I feel his attributions regarding the age of some of his pieces is sometimes off of what I would think, but he is anyway handling "genuine" pieces, and should definitely be able to put you on the right track.

To my experience you should avoid paying "much" for anything since the risk of buying a fake is greater the higher the price. If you are offered "Imperial Ming pieces cheap" I suggest you do yourself a favor and forget it, since the chance of buying anything under it's actual value is next to nothing.

There is a lot to be said here, but I would advise you to buy pieces you like and try to avoid anything seriously damaged, since they will turn out hard to sell should you ever want to.

I have been to Shanghai several times and like the city very much. There are a lot of good pieces around but they are hard to spot among all late copies and fakes even for an expert.

As a final tip as for Shanghai - there is often freewheelers approaching you when you are browsing antiques markets. They often show you a blurred picture and say - Ming porcelain - very cheap - or something of that sort, and wants you to follow them somewhere. My advise is to ignore these guys, at least because if they had real Ming, they could afford a shop. If they show you a book with a picture of the piece in, that book is possibly the source the piece has been copied from.

As for sure signs of authenticity, there are a few things you can try to notice. One of them is that porcelain jars and vases from the Ming and also the Qing dynasty is often heavier than their modern copies. But as always, this only holds true as long as the copyists does not know that we know... Just keep this in the back of your mind since it is hard to describe when it applies.

As for a key clue to "Ming" porcelain there is one feature I was told when I started to collect. It is a very simple thing and has to do with the fact that the Chinese changed the source of Kaolin clay by the end of the Ming dynasty. The Ming clay bodies seems to contain an iron impurity which makes the unglazed parts of the porcelain body to turn into an rusty iron color when fired. This rusty red color is often seen where the glaze stops short of the foot rim. Most old "minyao" porcelain usually also have glaze flaws where the glaze is not entirely covering the body. Those places and the foot rim is where to look for this rather nice discoloration.

This helps but is not infallibly. Copyists sometimes cover unglazed parts of their pieces with some brown or reddish goo to fool those who have heard that old pieces should be reddish brown where the porcelain body is exposed. So, use this with some caution. In time you will notice that this "iron" content give Ming pieces an overall "warm" look that could be recognized and separates them from other porcelain.

"Old" blue cobalt pigment have a tendency to go from dark blue to black and gray tones on "peoples ware" pieces. This is because the potters were using local cobalt that I believe also contained some iron. The touch of "blackish" is at least a good sign if you are looking for provincial Ming.

Modern late 19th century pieces is often decorated with an annoyingly dark, clear blue. Look for this on ginger jars with big characters on. They are not "worthless" only because they are of recent make, but sometimes they look "old" and I just think they should be recognized as what they are.

You should look at, but particularly, FEEL the glaze. Good pieces is very glossy and smooth to the touch. NEVER by anything if you don't like the feel of the glaze. This is basically the best rule there is. I think this has something to do with the fact that old porcelain was fired in wood fired kilns. It might also have something to do with the composition of the glaze, but this is too longwinded to go into. Modern porcelain have been fired with coal, or crude oil since at least 1949, which contains sulfur which actually damage the calcium in the glaze and gives it a "dry" feeling. This would hold true for most 19th and 20th century pieces that also can "look old".

Finally I would like to mention one absolutely worthless piece of advise you might find in some older texts on Chinese porcelain, and this is the mentioning of an “orange peel” effect to the glaze by which you should be able to recognize old pieces. This advise really sucks because the best old pieces, especially Imperial Ming, is absolutely perfectly smooth, and some modern pieces have an "orange peel" glaze because it has been applied by spraying. So forget that.

Finally, you can always send me a picture. Most porcelain pieces is quite easy to recognize for what they are. If you would like a second opinion on something please feel free to ask.

Jan-Erik Nilsson