By Jan-Erik Nilsson

Co-founder and member of the Initial Project Management Committee

The East Indiaman Gotheborg III - replica built 1992-2005 of the original Gotheborg

that foundered and sank at home coming just outside the home harbour in 1745

In 1731 Henric Koenig & Co was given the first Swedish Royal Charter to peacefully trade with "All Countries East of India". The most successful business was made with China, through the port city of Guangdong (Canton).

The East India Company turned Gothenburg into a flourishing merchant's city after it had been founded in 1731. Already in 1732 the first especially equipped 'East Indiaman' had been sent out to China. The China trade consisted of mainly porcelain, tea, spices and precious silks.

On their way to China, the Chinese had also wanted the Swedes to bring silver in the form of minted Spanish coins picked up in Cadiz, Spain. Often as much as 5 tons of silver was brought onboard. Upon arrival in China, tea, porcelain, silk and spices were traded towards the silver. The return cargo was shipped back to Sweden to be sold at auction in Gothenburg. The business was profitable and benefited both the Swedish merchants and the Chinese export trade and industry for more than 80 years to come. This set the stage for a new era of trade and intense cultural interaction between the two countries and regions.

During this period the Swedish company made 132 voyages between Gothenburg and Guangdong (Canton) in China, sometimes touching in India. Most went well but sometimes disaster struck - as with the East Indiaman Gotheborg in 1745. During the period eight ships out of all in all 38 East Indiamen were lost.

Every winter one or several ships was outfitted and sent to China or occasionally to India, to try their luck in having a safe passage, obtaining a profitable cargo and bringing the ship and its crew safely back to its eagerly awaiting shareholders, investors and loving families. The voyages were dangerous and by far not all of the crew came back alive. Not even all the ships made it all the way back. The most surprising and spectacular disaster ever to strike the Swedish East India Company occurred the 12th September 1745 when the Gotheborg on homecoming from China struck on a well-known reef and sank with the home harbor clearly within sight. No documents explaining this accident have ever been found. It has even been speculated that she was purposely put aground. This rumor has caused endless speculations about smuggling and hidden treasures and the full and true story indeed remains to be told..

2.1. The journey to China

A round trip journey from Sweden to China usually took some 17 - 20 months if the winds were favorable and if there was no need to sit out the monsoon period. If economy or climate forced the ship to wait til the trade winds changed, the voyage could take up to 26 - 31 months. If the ship left Gothenburg around January to February, she could be at Java around July or August. Here, the direction of the monsoon winds would be critical and even August could be too late in the season. The trip from Java to China should take around a month. To unload, one month and to load the return cargo should take from mid-September to the end of December, after which she could leave China and return to Sweden to arrive back home by June the following year.

2.2. The ship

The first East Indiaman Gotheborg was built on the shipyard Terra Nova in Stockholm and had a cargo capacity of c 843 metric tons. She did her first voyage during the 7th expedition 1739-40 and was then auctioned to the 9th expedition for 84,000 Daler Silvermynt. She seemed to be in good condition.

To help visualize what it could have looked like onboard an 18th century Swedish East Indiaman we have the diary of the Ships' priest, Jacob Wallenberg, who in 1769 left his impression from a visit onboard the East Indiaman Finland.

Furthermost aft, Wallenberg tells, was were the officials' cabins and the medicine chest, which also doubled as pulpit for the priest on Sundays. From there on, along the larboard corridor came the deckhand's' hammocks; the second table where 'better food was eaten' and then a smaller table where the cadets (mid-shipmen) 'had their peas'. On the right side stood some fifty sheep and on the other side, goats, pigs and a cow from Hisingen whose calf had already 'ventured into eternity'. From the cow, they got milk. Further forward was the smoky kitchen, where the foremost hearth was for the table of the masters and in a huge copper bucket, all the rations were boiled for the crew.

Immediately in front of this was the galleon, the 'bathroom' for the 150 strong crew. The starboard corridor led around three oxen, the anchor rope and 'there among the chests were the mid-shipmen and the carpenter'. Somewhere around there, the story is interrupted as the stench forces Wallenberg up on deck again. (Wallenberg, Jacob. Min son på galejan, 1769).

2.3. To Cadiz in April 1743

Gotheborg arrived at Cadiz the 7th April 1743 and stayed there for a full month. Taken onboard were provisions and silver and wines and a medical chest to be passed on to Riddarhuset. August Tabeauteu, the 'Premier Supracargo' and highest in command onboard, also brought onboard a mason and had him make an oven. It was not until the 6th of May 1743 that they continued their voyage.

2.4. Rounding of the Cape of Good Hope on outgoing

Next stop was Java where there was fresh fruit that provided a cure for scurvy, a disease that made the gums swell and eating of salty food painful. By then the men also craved something sugary and sweet but the access to so much fruit was not entirely risk free, "The vast amount of fruits eaten caused a marrow sucking bowl movement that threatened to take with it, both cheek bones and stomach" (Wallenberg, 1769). Gotheborg rounds Cape and arrives at Java on 28 August 1743 with the crew were in very poor condition. Due to contrary winds they are delayed here until the next year.

2.5. Arriving at Canton September 1744

The first sure note we have for their actual arrival to China is from the 8th September. This consistent delay suggested that they had some kind of problems. A large part of the crew were deceased by then and a further number of them were sick. They also could have had problems with the perpetual upkeep of the ship which was a large part of the traveling. Private business ventures could also have been ongoing that slowed down her voyage.

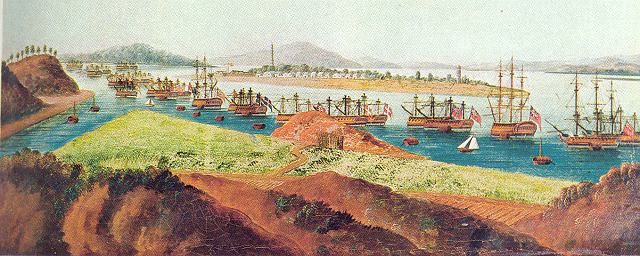

Wampoa anchorage in the Pearl River close to Canton, c. 1760

Painting in the collection of the Gotheborg City Museum.

2.6. Departure from Canton in January 1745

The voyage from Canton to Sweden was no less troubled. When exactly the Gotheborg left Canton is unknown but she presumably left together with the Riddarhuset, which departed Canton 10 January 1745. 35 new men were mustered as new crew where there were many Swedes and Dutch in Canton and Java who might have been grateful for an opportunity to return back to Europe.

The ship was loaded, where furthermost down, the ingots of Tutanego were placed (a mixture of copper and zinc) on top of which lay porcelain, both heavy and waterproof merchandise. This created a floor on top of which tea and silk could be placed. Under over, beyond and around this, and literally placed everywhere, was private merchandise and things that were bought cheap and possible to sell at a profit, until the ship was 'filled up like an egg' (Mattias Holmers)

2.7. Dover, the English Chanel

By the 6th of September, both Riddarhuset and Gotheborg arrive to Dover in England. After a long and trouble filled voyage, both ships were in serious need of repair and new provisions. They took onboard each a pilot for the remaining of the trip and against 80 British pounds of payment the pilots Ellin Paskill and John Earl were to show both ships back home to Gothenburg. By the 11th of September, Norway's southernmost part is in sight.

2.8. Gothenburg the 12th of September 1745

The East Indiaman Gotheborg, the pride of the Swedish East India Company, approached land. But then, for no apparent reason, she struck onto the well-known underwater reef, the Hunnebådan, just alongside the main navigation channel and a mere 900 meters from the fortress of Nya Elfsborg. The impact was violent. The whole of her bow was crushed upon the rock, where she lodged fast with her aft under water. No one though appears to have lost his life, and by good fortune a start could be made at once to recover her cargo.

The Gothenburg shipwreck was located close to the Gothenburg harbour and everything on board that could be salvaged was probably salvaged soon after the foundering in 1745.

According to contemporary documents in the Gothenburg City archive, wet tea was dried in available baking ovens in the city "after which an unprecedented invasion of huge, newly hatched, roaches invaded the city". Since the porcelain chests were according to standing orders lining the bottom of the hull a considerably amount if not all was left where it were, under tons upon tons of soggy tea, 'gallingall' and broken chests.

In later salvaging attempts during the 19th century, additional small quantities of porcelain were recovered. Johan Kjellberg, diving in 1860s succeeded in taking up 77 dozen pieces of porcelain and Captain Lampa and James Bourn, according to newspaper reports from 1877, recovered "a lot of porcelain… consisting of tea and coffee cups and saucers, large and small places, tea and coffee pots, etc".

By the time of the mid 19th century the old oak hull had now blackened and become attractive for making furniture. Several attempts were thus made to bring up as much as possible of this hard and valuable wood. To this end several diving companies approached the wreck and at least some of them seemed to have used dynamite to pry the hull apart. In 1864 and 1876 pieces of oak were salvaged from the wreck and some amounts of porcelain.

In 1905, James Keiller, a member of one of the distinguished Gothenburg families of Scottish descent, and Carl Lyon, an antique dealer, obtained royal permission to salvage what could be left of the wreck. The salvaging continued over the summers of 1906-09 but could due to the previous blastings of the wreck only recover around 3,000 undamaged porcelain pieces 'within an area sized as a football field, covered with shards'. After this 'nothing' was believed to remain of the ship and the wreck site was forgotten again.

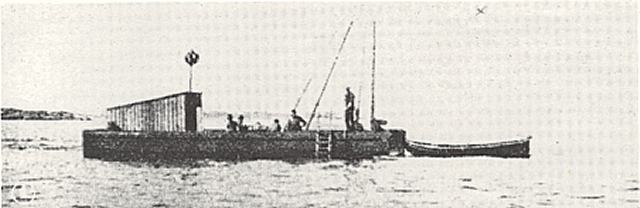

Photo: 'Hwar 8:de Dag', 1907.

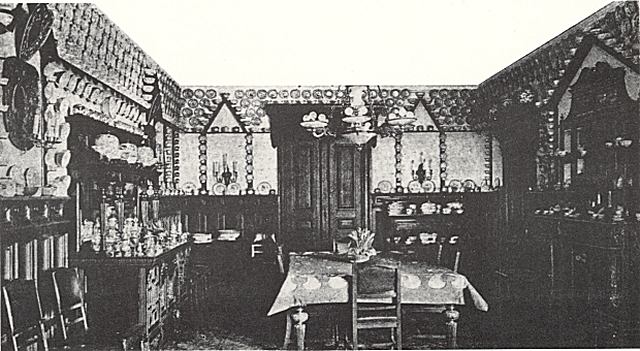

Of the recovered pieces a large proportion were medium sized fruit dishes in blue and white. Teacups and saucers of 'eggshell thinness' are mentioned in early reports from the salvage operation while the full total of undamaged eggshell tea sets from the Gotheborg might well be less than a few dozen.

The dining room at the Keiller family residence at Särö, decorated with a selection of the finds.

Photo: 'Hwar 8:de Dag', 1907.

In 1986 after having rediscovered the wreck site and obtained the necessary permits, the diving instructor and his wife Anders and Berit Wästfelt started a full-scale marine archaeological excavation of the Gotheborg that over the years would get the attention of the whole world. This got its continuation in October 1992 when they launched their idea of building a full-scale sailing replica of the Gotheborg I which was to become the Gotheborg III project.

In the excavation years of 1986-1991, less than 300 complete items and 6 tones of porcelain shards were found. The only structured analysis so far made of the cargo of the East Indiaman Gotheborg was made by Berit Wästfelt published in The porcelain from the East Indiaman Götheborg (1990). In this book Wästfelt analyze the blue and white part of the cargo based on the remains of the cargo found during the excavation. The complete items were much too few to represent more than a very small part of the cargo. Most of the analysis was thus based on the shards, where the first challenge was to reconstruct the occurring patterns.

From the cargo list of the ship they knew the Gotheborg had carried 289 chests, 12 tubs and 238 bundles of porcelain, weighing all in all around 100 tons, this all in all probably being between 500,000 - 600,000 pieces. Any description of the actual content of these chests and bundles has not been found so far.

From the sea, tons of porcelain shards were picked up. And the findings were brought to the base camp at the Fortress of New Elvsborg, for registration and preservation.

The second largest part of the cargo as represented by the excavated shards was porcelain with underglaze blue decoration combined with an all covering brown iron based glaze on the other side. This type of wares are usually called 'Café au lait' or 'Batavia' and in this sample proved to be less sturdy than the sole 'blue and white' part, and had to a large extent lost its gloss. When the 'Batavia' brown glaze surface eroded over time, it seems to have made a good ground for barnacles and clams to live on and a large number of brown glazed shards were found with encrustation particularly covering the brown glazed surfaces.

One special variation of polychrome decoration called 'Chinese Imari' was found on around 10% of the shards from the excavation. The Chinese Imari decoration was defined in Berit Wästfelts report as porcelain with a combination of underglaze blue cobalt and on-glaze enamels of which mostly appeared to be iron red and gold. Quite a number of shards with their enamels intact were found to merit this classification and to establish the normally occurring decorations. Traces of the iron red colors could often be seen in outlines and in rare occasion, traces of gold.

Naturally the enamels were corroded and degraded by salt water and sand that had twirled around the shards in the streaming water around the wreck site. Most of the enamels were, due to these processes, lost. From the excavation report it is thus not possible to see if some of these shards classified as Imari could in fact have been 'famille verte' or wucai type decoration with underglaze blue combined with transparent enamels.

Since the overwhelmingly large majority of the cargo was tea, shards of enamel decorated porcelain pieces could be found within layers of soggy tea, with completely preserved and intact colored enamels which further strengthened the analyze and classifications groupings. These shards were also used as reference to a group of enamel decorated shards that was re-fired, enamels that turned out pretty much the same as the originals.

Besides the above decoration types, small amounts of a more rare decoration such as 'powder blue', sometimes with added decoration in gilt and lacque burgatau, which is porcelain covered with lacquer with inset Mother of Pearl. A limited number of totally white undecorated pieces of porcelain seemed also to have been brought in. One type that occurred in small amounts was the variation often called 'soft paste'. Shards classified as this was distinguished by being thinner, whiter in shade and having extremely well painted decoration often under a crackled blue and white glaze. A special group was small figurines as small dogs, incense burner stands and water droppers, and small, seated Chinese boys. To a lesser extent parts of tea sets or dinner sets with specially ordered decoration was also found. Surprisingly, no dinner set parts except two large dishes were found among the blue and white porcelain.

In sum, more than 100 motifs were possible to reconstruct of the blue and white porcelain. Some of the motifs took more than 4 years to find enough shards to make a complete motif.

Following the footsteps of the excavation, a long series of exhibitions was set up in Sweden and in Asia. 6 tons of Chinese porcelain shards had been brought up and studied with some 260-year-old tea tasting to be perfectly honest, mostly - mud. The scientific results had been presented in articles, in books, in seminars and in thousands of public lectures. In 1991 exhibitions with the finds were held in Hong Kong and in 1992, in Singapore and Shanghai.

In 1992 the plan of building a replica of the first East Indiaman Gothenburg was presented. A Project Management Committee was organized to voluntarily and initially run the project. The idea met with enthusiastic support by the local small industry while the major Swedish export industry with few exceptions remained cautious. The hull was constructed as historically accurate as possible outboard as well as inboard above the free board deck.

From the very beginning the ambitions were to use this unique project for many different ends within industry, trade and culture. The practical goal was to build, equip and send this ship with a well-trained crew around the Cape of Good Hope and back to symbolically reopen the old trade route to China. We estimated that the trip would take about 18 months and, we were also to make sure she would not strike on a rock again, on homecoming.

In 1993 the interest from the public to financially support the East Indiaman project was overwhelming. The gratitude that should be granted to all and everybody involved in this visionary and exciting project is immense.

Jan-Erik Nilsson

Co-founder of the Gotheborg III Rebuilding and Voyage Project.

Member of the Initial Gotheborg III Project Management Committee

Link suggestion: The Gotheborg III Project