LIAO907 - 1125 |

|

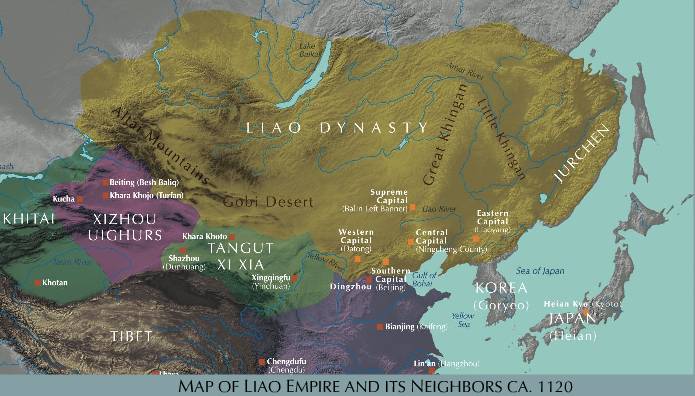

The Liao were Khitan Mongols. Before 936 A.D. they lived in the area between present days Beijing and the sea south of the Great Wall. In 946 A.D. they established the Kingdom of Liao which by 1120 covered a wide area of Northern Asia including Mongolia and Russia beyond Lake Baykal and Nothern China. The dynasty was contemporary with the first half of the Song Dynasty ruled from Kaifeng. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Liao empire was the most powerful regime in East Asia. It developed broad contacts with the Korean and the Japanese on the east; the Song Chinese in the south; and the Uighur and Tangut people in the west. Through extensive routes inland and via the sea, the Liao’s trading network further extended to India, West Asia, and the Baltic Sea.

Luxuries and Necessities

The Liao culture was international to its nature which is testified by an abundance of luxury wares found in Liao tombs. The tomb of the Princess of Chen and her husband, Xiao Shaoju (dated 1018) contained glass vessels and a large bronze basin imported from Iran and the Near East, amber from the Baltic Sea, rock crystal from South or Southeast Asia, and jade possibly from Inner Asia. Foreign stylistic elements are visible on a number of the objects from this tomb, such as C-shaped gold bracelets with animal terminates, which were first developed in the Near East. Beaded necklaces strung with spacers originated in India and were often used on Buddhist statues during the preceding Tang dynasty.

Frequent contacts with the Jurchens, Tanguts, and Uighurs enabled the Liao empire to acquire a rich variety of resources ranging from horses and falcons to Buddhist scriptures, jade, and precious metals. The Liao rulers also received tribute annually from the rulers of Song China in the form of large quantities of silver taels and silk. With this steady income of wealth, the Liao elite could afford to buy luxurious commodities from Song artists, including the delicate Yue celadon wares from Zhejiang and fine white and green wares from Shaanxi and Hebei provinces.

Skilled local and foreign craftsmen produced functional objects within the Liao territories, as well as specialized goods and adornments for the elite classes. The production of ceramics was particularly important; kilns were built in areas around the capital shortly after the empire was established to help fulfill local demands. Potters created a number of ceramic forms in imitation of gold and silver vessels or based on wood and leather prototypes for use on horseback. Colorful lead glazes decorated many of these high-fired clay roof tiles, Buddhist sculptures, and vessels.

Liao ceramics are unique in form, glaze and design but are of an original Chinese technique though some forms show Tang influence. Liao ceramics are often monochrome white and black - similar to Cizhou wares of the Yuan dynasty while other might bear a strong resemblance to Tang sancai lead glazes; the most differences are in the shapes found typically based on leather shapes and metal.

The Nomadic Heritage

The Khitan rulers continued to value their nomadic heritage even after the establishment of the Liao dynasty. The horse was the most valued animal in Liao society as it provided not only mobility but also food. Skills common to Khitan nomads such as hunting and archery on horseback are also reflected in the discovery of hunting tools such as awls, sheathed knives, bow cases, and arrows in Liao-dynasty sites. Falcons, an integral part of Khitan culture, were also still trained for hunting purposes.

The link between the Liao-dynasty elite and their Asian steppe roots is also evident in their distinctive mortuary practices. These included careful preparation of the corpse by wrapping the limbs in silk and clothing the body in metal burial attire, consisting of a face mask, body netting, and shoes. Burial attire could include a silver mesh burial suit, gold face mask, and gilded-silver boots (found belonging to the Princess of Chen). Small, yurt-shaped earthenware funerary urn took its form from the traditional circular tents used by Khitan nomads.

Other ceramics from Liao-dynasty tombs also indicate the survival of forms related to the Khitan’s nomadic heritage. For example, a bottle in the shape of an ox leg was derived from a traditional form used for fermenting milk or storing wine. The nomads' use of animal skins to make functional vessels is evident in the shape of distinctive bagshaped flasks based on leather prototypes - materials such as leather or wood were particularly suitable for a mobile lifestyle. That vessels originally created from such practical materials were transformed into freestanding ceramic flasks reflects the amalgamation of the nomadic and sedentary ways of living that characterized the founders of the Liao empire.

The Chinese Tomb Tradition

The Liao-dynasty tomb structures and their funerary contents indicate an integration of certain aspects of Siberian steppe burial tradition and Han Chinese tomb traditions with unique Liao Buddhist funereal practices. In China, the structure and interior decorations of a tomb along with its burial objects were consciously constructed to create a "personal universe" for the deceased. For centuries prior to the Liao dynasty, the Chinese built their tombs in imitation of underground shelters for the living, based on their beliefs in and ideas of the afterlife. The structure of Liao tombs relates to this mortuary tradition.

Similar to a typical Han Chinese tomb, the interior of a Liao-dynasty tomb, was often painted with images of attendants and objects relating to the life of the deceased in an attempt to construct a familiar afterlife. Many tombs also contained provisions to sustain the "life" of the deceased after death and written messages to enable communication with the spirits.

As the Buddhist practice of cremation became prevalent in the Liao empire, wooden boxes were used to contain ashes of cremated Buddhist monks. Similarly, life-size wooden mannequins made of movable sections, functioned as containers for cremated ashes that were inserted into an opening in its chest. This novel method of inserting cremated human ashes into a wooden mannequin was a Liao invention that integrated Buddhist cremation practices with the historical Chinese conception of the afterlife, which necessitated the preservation of the body.

Religious Life

Four systems of religious belief prevailed within Liao society and sometimes intersected in their devotional practices: Confucianism, Daoism, Khitan shamanism, and Buddhism. Confucianism and Daoism were primarily limited to the Chinese territories acquired with the expansion of the Liao empire and to some Liao state rituals.

State shamanic ceremonies and sacrifices were performed by special court officials. Most members of Khitan tribal society continued to worship local spirits and supernatural powers and to practice shamanism and divination using animal bones.

The Liao rulers were also great patrons of Buddhist temples and monasteries and favored the spread of the religion in the southern regions through the printing of religious texts and the inscription of scriptures on stone steles.

Liao Buddhists believed that in 1052, the Buddhist religion would come to the phase of "final dharma" when the three treasures of Buddhism - namely the Buddha, the dharma (law), and the monastic community - would be extinguished. As part of the imperial endeavor to prepare for the final dharma, a relic deposit was built at the White Pagoda, completed in 1049, located in present-day Balin Right Banner, Inner Mongolia. During restoration between 1988 and 1992, over one thousand items were discovered in the pagoda’s relic deposit. Among the many objects discovered were 109 pagoda-shaped containers, each of which contained sutra scriptures. Such deposits were connected with relic veneration, as the Liao Buddhists believed scriptures were manifestations of the invisible Buddha body or the Buddhist dharma.

The worship of texts with a particular preference for the Great Dharani Sutra of Stainless Pure Light was a distinctive feature of Liao-dynasty Buddhism that differed from Song dynasty practices. This unique conception of Buddhism under the Liao indicates a connection with contemporary Korea where there was a similar tradition of text veneration. While scriptures were a particular focus of Liao Buddhist veneration, sculptures of free-standing Buddhist images were also erected by believers in the Liao empire.

Chinese archaeology has revealed various types of Liao Buddhist sculptures, ranging from votive stone sculptures of Shakyamuni Buddha and bodhisattvas made of sculpted earthenware, to high-fired sculptures in white glaze, as well as those with colorful lead-glaze.

Downfall

From the mid 11th century a period of corruption and violence signalled the downfall of the Liao dynasty. In 1120 the Jurchen destroyed the Liao Dynasty's Supreme capital and eventually caused the collapse of Liao political and military leadership. In 1125 the Liao empire fell to the Jurchen, who also captured the Chinese capital at Kaifeng (formerly Bianliang), forcing the Song court to flee South.

The text is based on, CHINA - a Country Study by Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, Edited by Robert L. Worden, Andrea Matles Savada and Ronald E. Dolan. Research Completed July 1987. Asia Society and Museum, New York Exhibition 2006, Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China's Liao Empire (907-1125). This version and Webpage © Jan-Erik Nilsson, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2002 and 2008